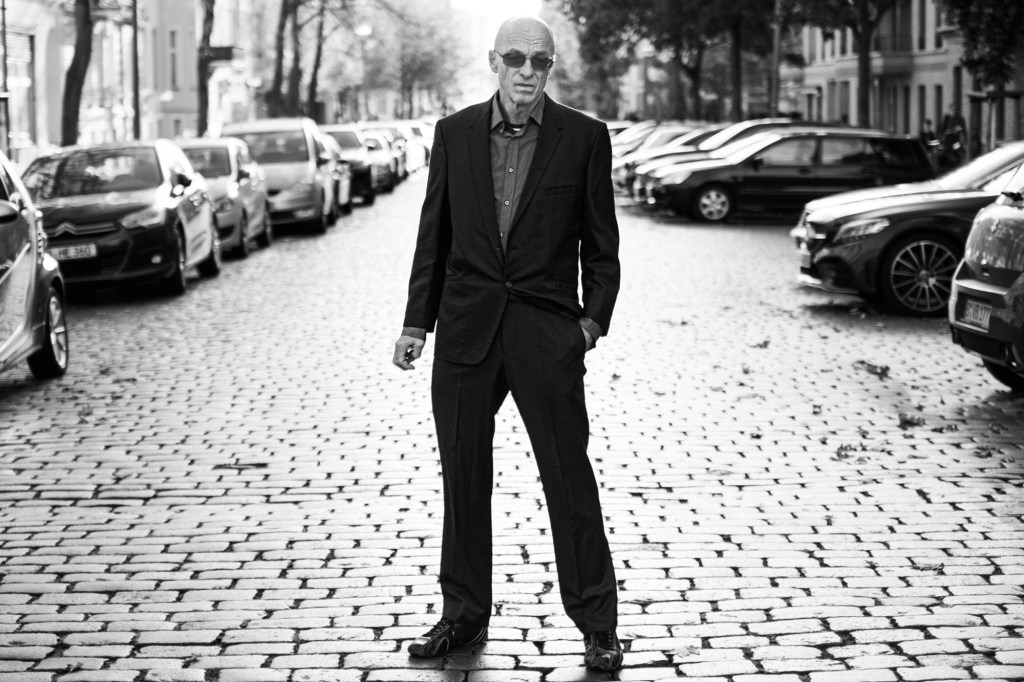

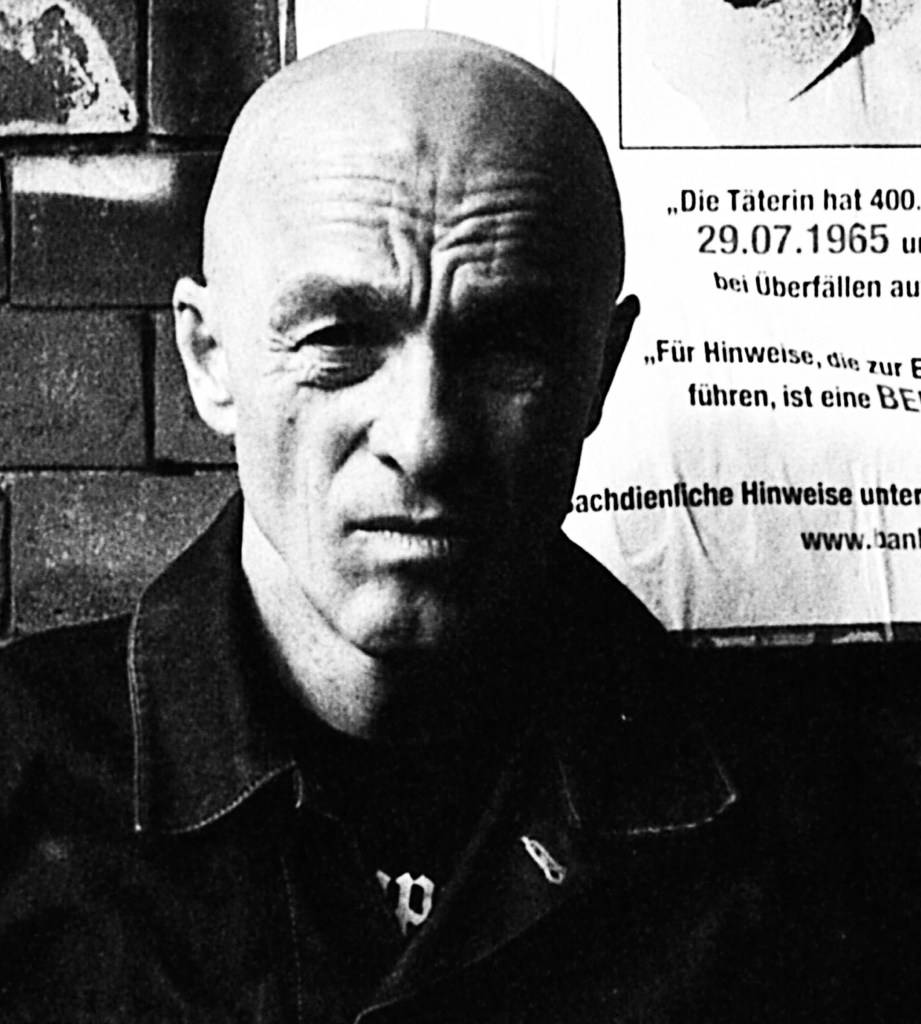

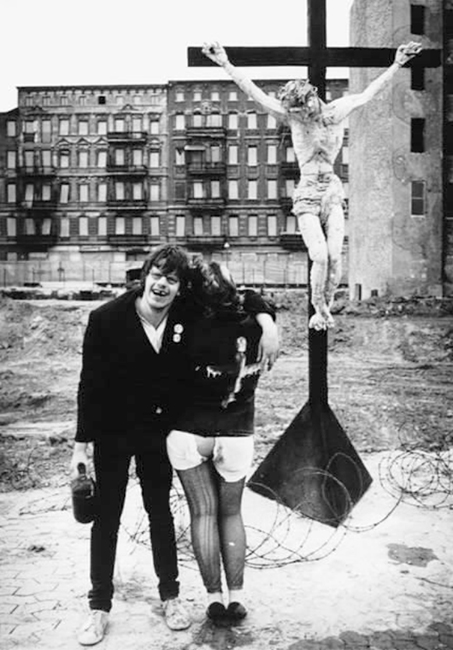

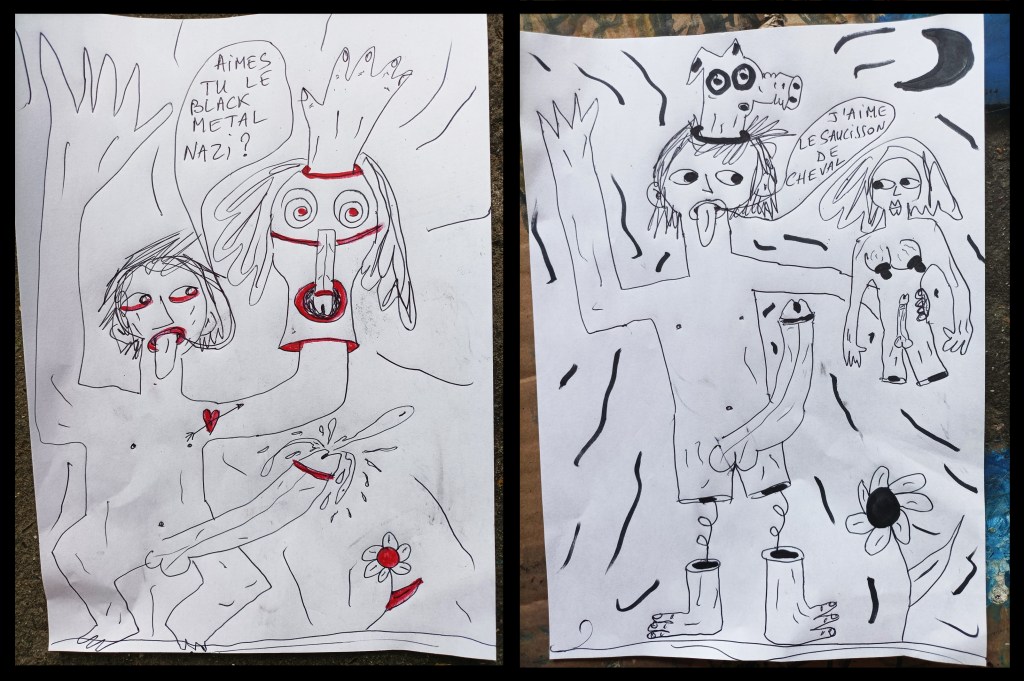

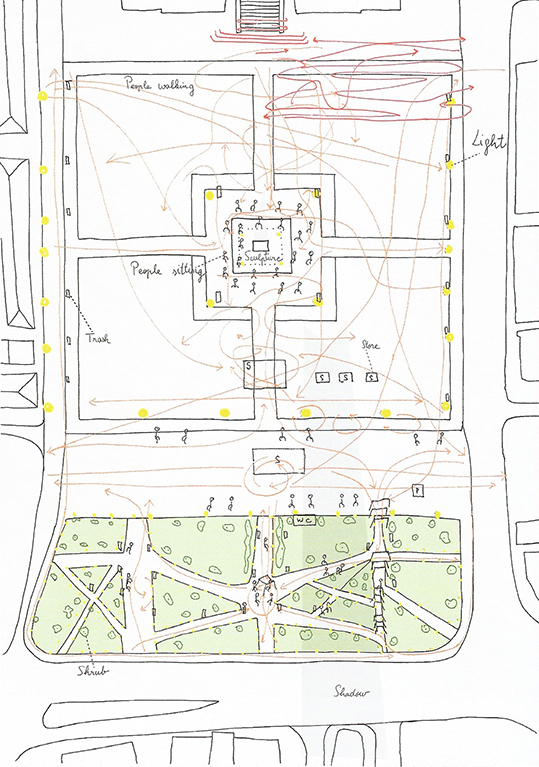

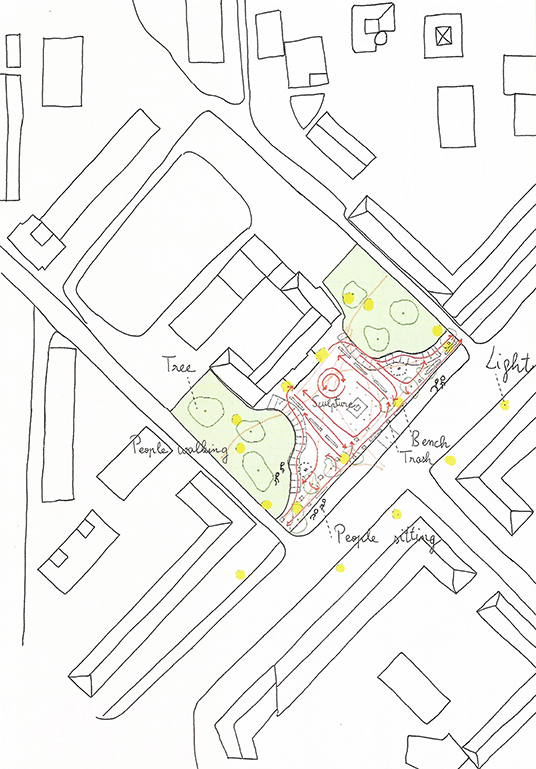

Photographié par REAP, Marseille, Février 2022

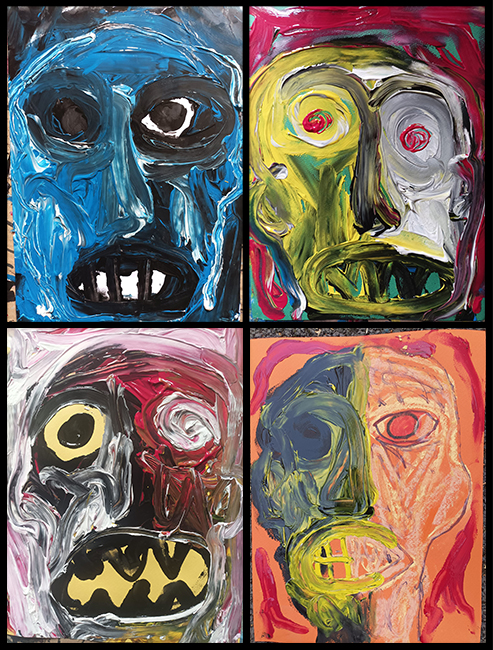

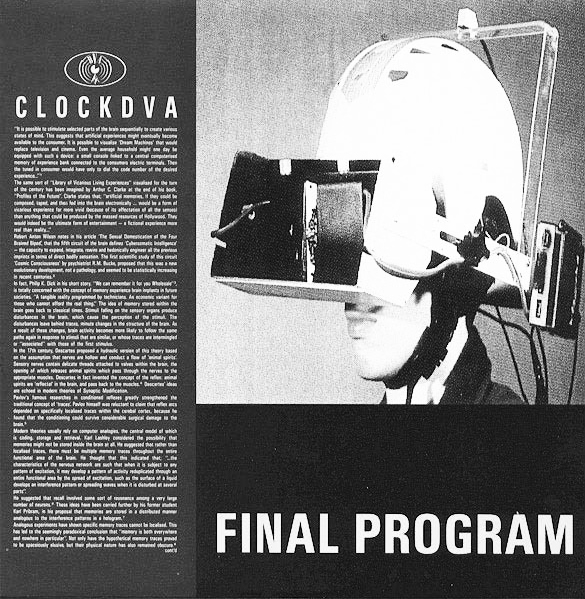

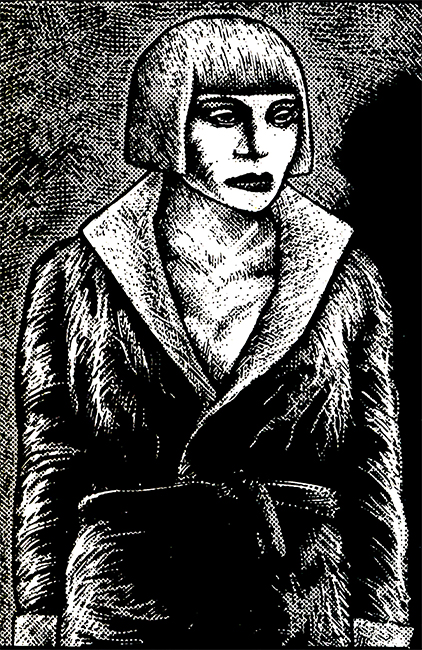

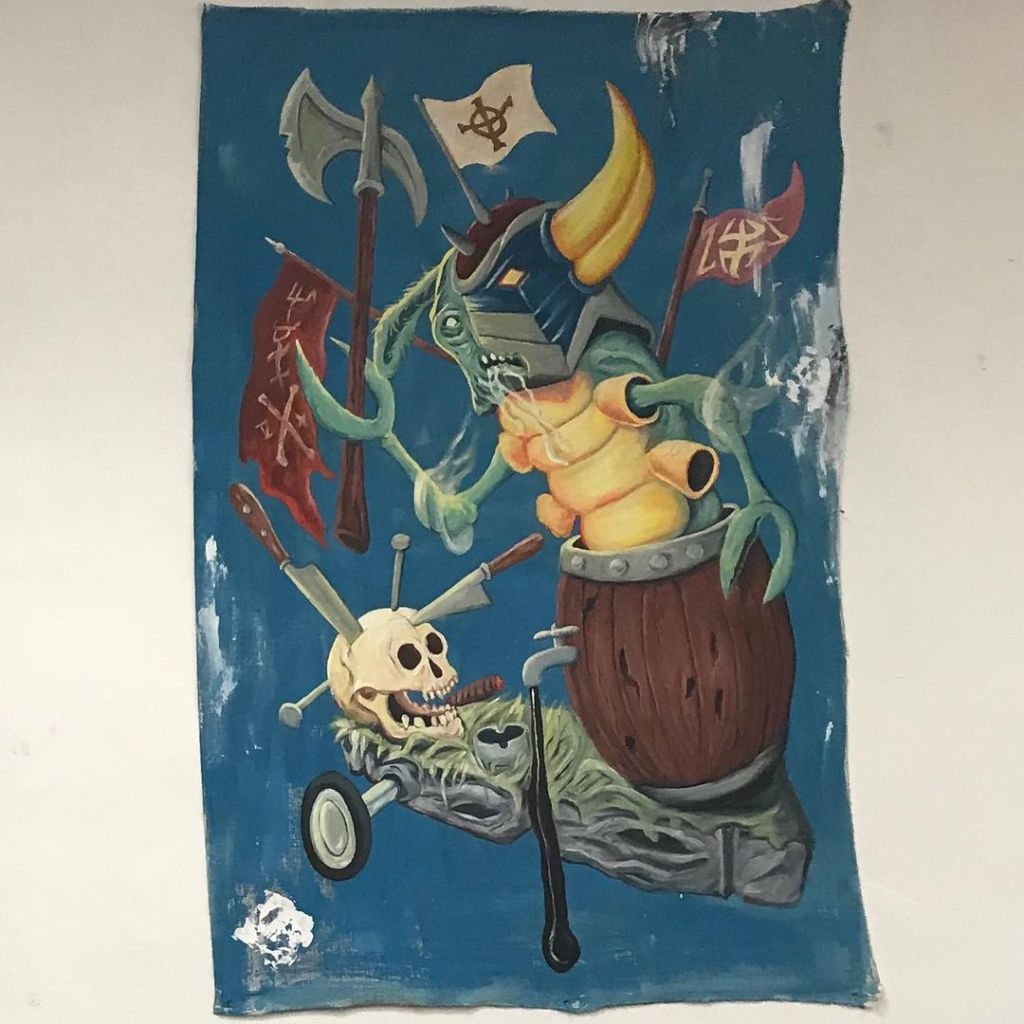

“Un château perpétuel est un vortex, une méta-peinture sans limites de dimensions ni de bords où l’ héritage dadaïste, expressionniste et médiéval se colisionnent avec d’ anciennes cultures et d’ autres plus modernes dans une vision fantastique.

Un château perpétuel est un fleuve de papiers peints puis découpés, un flux continu de peinture comme une fin en soi qui ne propose pas un résultat mais de multiples formes et combinaisons.Un château perpétuel se développe et étend son espace au gré des pinceaux et de leur fantaisie. Dans un chateau chaque élément fonctionne en lui même comme dans un tout fractal. Quant-au peintre d’ un château, il s’ y trouve comme Alice au pays des merveilles, il rêve et fabrique sa réalité en même temps qu’ il la traverse. Dans un château perpétuel, un peintre ne s’ autorise pas de s’accompagner de croquis préparatoires, pas plus qu’ il ne se permet une esquisse sur les supports.”

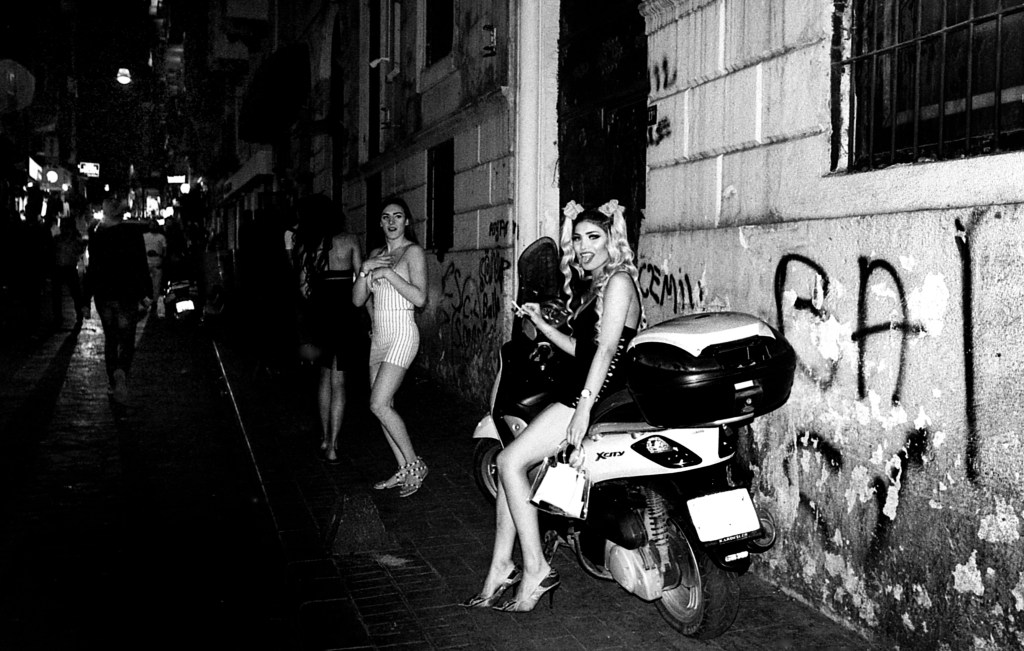

Photographié par REAP, Marseille, Février 2022

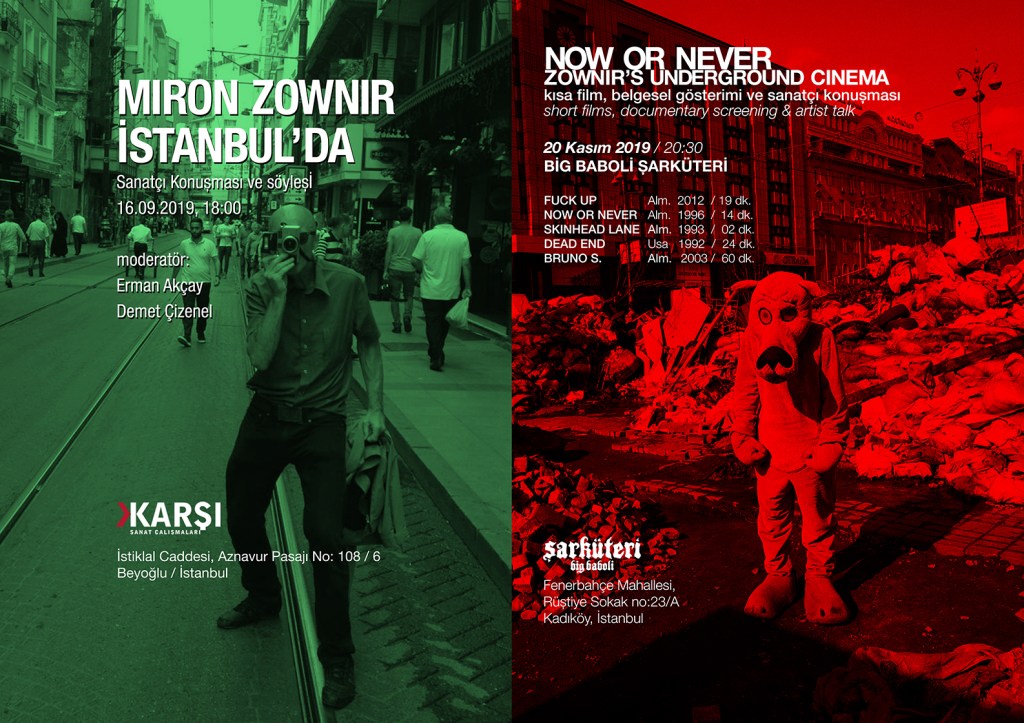

Bonjour Dave, après une longue pause, j’espère que vous pourrez nous accorder un peu de temps pour avoir une petite conversation spécialement lorsque vous serez de retour dans le cyberespace avec vos aquarelles. Tout d’abord, merci beaucoup pour vos efforts et votre soutien pour notre exposition collective “Retina Decadence” il y a 2 ans. Malgré la faible participation due à la pandémie, l’exposition a été l’un des jalons de l’histoire de l’art souterrain d’Istanbul. Nous n’avons toujours pas réussi à nous débarrasser des effets des vidéo-animations d’Acid TV.

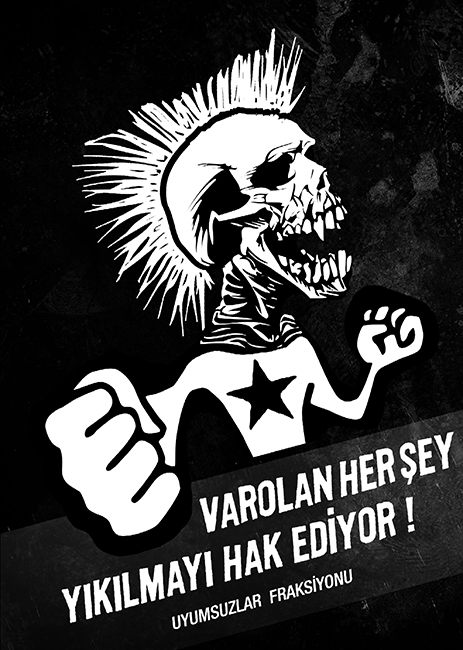

Malheureusement, la galerie a été bientôt fermée, mais les activités clandestines continuent à plein régime, et en tant que fanzine Löpçük, je fais de mon mieux pour créer une culture graphique critique anti-impérialiste.

Peut-on parler d’un vivre-underground computer culture aujourd’hui, où même le concept de « cyberpunk » s’est éloigné de son contexte et s’est transformé en une perception techno-fétichiste et s’est vidé ?

Il semble que la scène démo est toujours et contre toute attente encore extrêmement vivace. On peut y voir des choses artistiquement significtatives par exemple dans les compétitions de démos limitées à 4kb octets. Pour donner un ordre d’ idée un CV sauvegardé sous Word pèse entre 20 Kb et 30 Kb. Dans ces 4 Ko octets des orfèvres du code peuvent faire tourner : un moteur 3D et un contenu pour le moteur 3D. Ces démos sont de véritables performances, le code est au caractère près. C’ est de la pure poésie mathématique et syntaxique. Certains codeurs ont mis au point des moteurs 3D pour des ordinateurs “obsolètes” tels que des Commodore 64 ou même des ZX spectrum tandisqu’ il étaient considérés impossibles à programmer du temps où ces machines étaient utilisées dans les années 80/90. C’ est un point important ici et qui fait écho à l’ émergence des IA génératrices d’ images (Midjourney, DALL E 2 …). Ces IA sont proposées à qui le voudra pour jouer le rôle de “directeur artistique”; il s’ agit d’ écrire une simple phrase qui sera ensuite interprêtée par l’ IA qui produira une image faisant appel à des supercalculateurs dont l’ énergie nécessaire au fonctionnement est celle d’ un avion de ligne à sa vitesse de croisière.

Pour en revenir à nos coders architectes des mathématiques ils ont le rôle inverse de ces IA dopées aux supercs aclculateurs en codant aujourd’ hui des programmes inconcevables dans les années 80, non pas car la technologie n’était pas assez avancée pour les concevoir – un Commodore 64 est aujourd’ hui le même qu’ en 1982 – mais bien par les progrès de la connaissance humaine en matière de programmation, non par un progrès technologique. Ces rétro demo makers sont les anges maudits des industriels du tout numérique leur philosophie n’ étant non pas le progrès en ligne droite de la technologie (et jusqu’ au mur s’ il le faut) mais la compréhension des technologies qui furent en place puis trop rapidement – progrès oblige – mises au rebus et sous exploitées.

Ces demo makers proposent le progrès de la connaissance et une certaine humilité dans le caractère dit “obsolète” du matériel employé tandis-que l’ industrie propose une course à l’ armement technologique explosive infinie dans un milieu fini. Choisis ton camp camarade, surtout si tu as des gosses : )

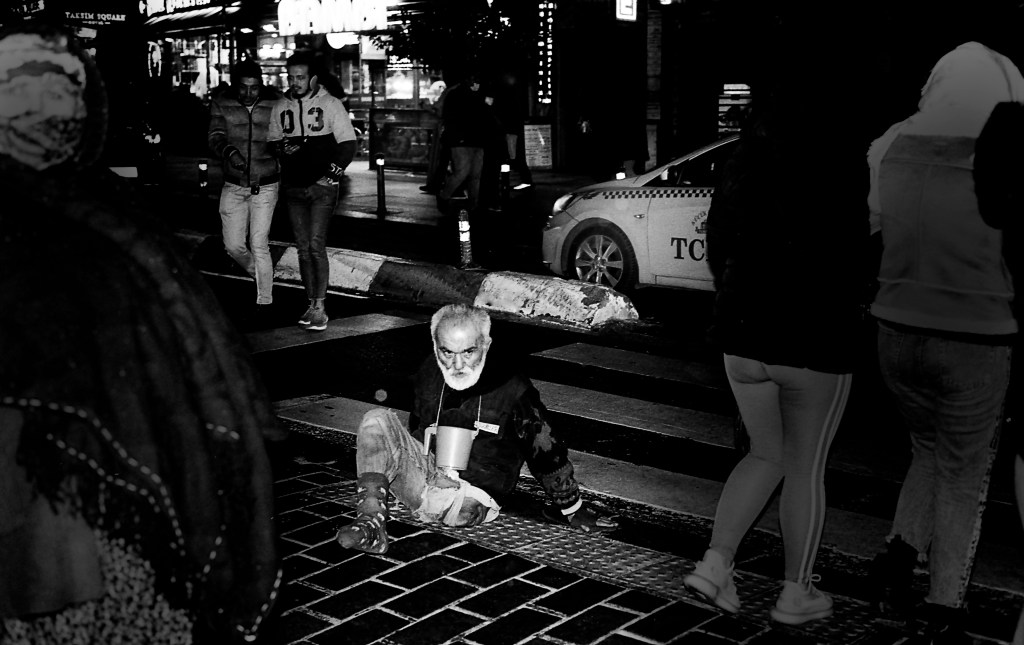

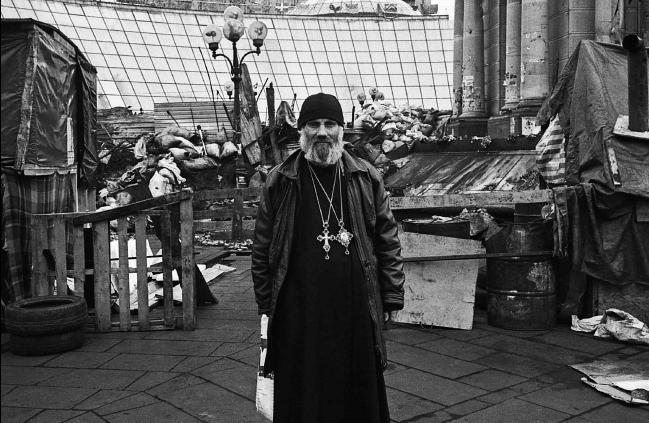

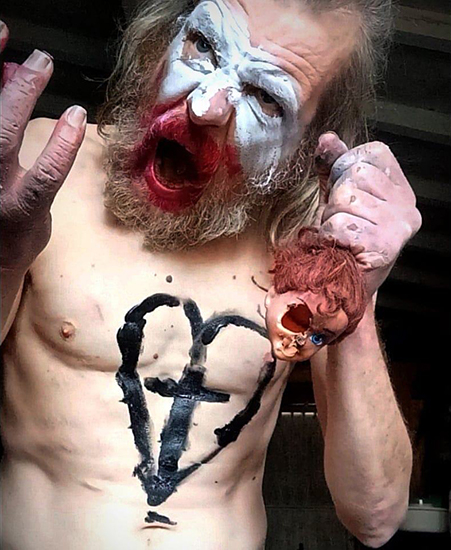

Photographié par REAP, Marseille, Février 2022

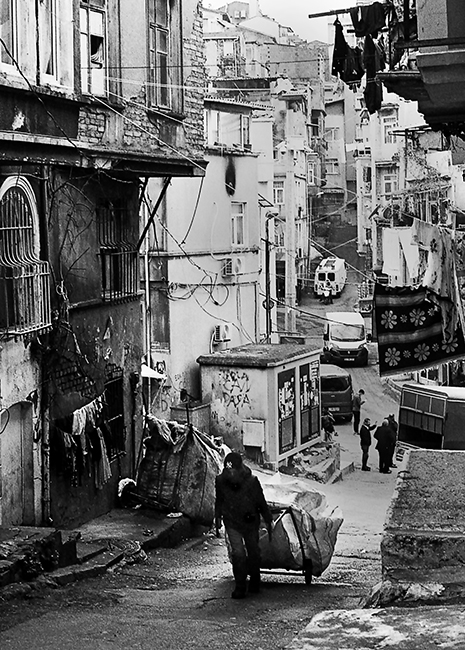

Photographié par REAP, Marseille, Février 2022

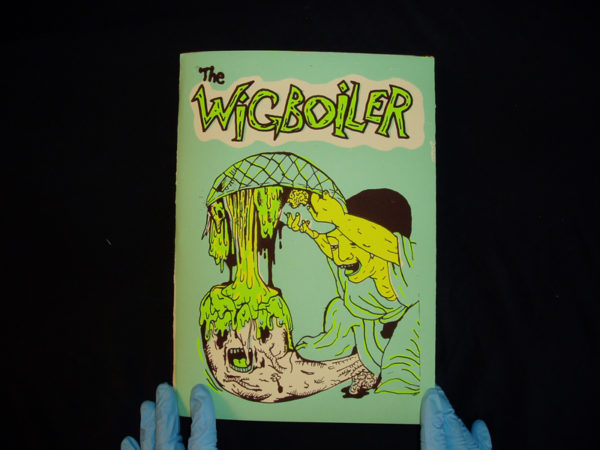

“Après, vous n’achèterez jamais plus le paquet de bandes dessi nées à la con que vous lisiez d’habitude” ,avait écrit Willem. illustre dessinateur et caricaturiste, notamment dans les colonnes de “Libé”, à propos du “Dernier Cri”.

Un “graphzine” à qui. à Sète, jamais à court d’idées quand il s’agit de mettre en relief les arts graphiques modernes (qu’ils oient brut ou rock’n’roll), Pascal Saumade a ouvert les portes de la “Pop Galerie”, quai du Pavois ‘Or. Et ce en marge de l’exposition “Mondo Dernier Cri, une Internationale Serigrafike” présentée au Miam.

En tant qu’artiste de la vieille école, comment évaluez-vous les sous-cultures actuelles des jeunes par rapport aux années 90 ?

Les sous-cultures se numérisent, comme à peu près tout ce qui peut être convertie sous forme de “0” et de “1”. C’ est un constat factuel. Le numérique ne complète plus, il remplace. Les sous-cultures numérisées sont comme tout ce qui est numerisable et en conséquence révisionnable, censurable par ceux qui ont la main mise sur les serveurs. Alors maintenant que je suis barbu comme un gandalf je pense que la liberté et l’ énergie que j’ ai pu vivre dans les années pré-internet étaient bien entendu beaucoup plus riches de rencontres et de chocs artistiques intenses que ce qu’ il est encore possible de vivre aujourd’ hui. Il l’ étaient forcément d’ autant plus intenses que l’ accès à la culture – et encore plus aux sub-cultures – ne se faisait PAS par internet. Ce qui impliquait une durée, entre deux chocs esthétiques. Cette durée a été anéantie à l’ avènement des moteurs de recherche. Jusqu’ au milieu des années 90 nous n’ étions pas en fRance globalement équipés d’ internet, le monde n’ entamait alors que sa lente et exponentielle glissade vers l’ empire de la suggestion. Aujourd’ hui des algorithmes nous suggèrent de partout, nous manifestent ce que nous sommes censés aimer – ils le savent mieux que nous ou plutôt il ne le savent pas mais ont le pouvoir de nous imposer les opinions que nous sommes censés adopter. Les années 90 – 80 bien qu’ elles aussi numériques mais très peu connectée furent dispensées de cette machine à uniformiser les désirs et les comportements. Pour accéder aux sous-cultures il fallait par exemple envoyer de l’ argent et une lettre postale dans un pays lointain pour recevoir quelques semaines plus tard la démo de tel ou tel groupe. Ces groupes étaient référencés dans des fanzines papier eux même commendables de la même façon. Le façonnage d’ un goût artistique se faisait lentement, rythmé par les lenteurs de la poste, les limites des moyens financiers, les difficultés à contacter ces groupes obscurs et bien sûr le degré d’ ivenvestissement personnel (trouver des timbres étrangers, écrire une lettre et attendre un retour demandait un effort beaucoup plus conséquent que de cliquer des liens sur internet). Une démo se refilait de la main à la main entre amateurs locaux de la même musique générant du contact humain, de l’ échange verbal et un tissus culturel et social d’ initiés. Exactement le contraire du bazar illimité ultra suggestif d’ internet . La rareté et l’exception était le corolaire de l’ absence d’ un moyen de diffusion massive et nous étions suggérés et conseillés par des amis, des artistes, des amateurs forcenés, pas par des algorithmes appartenant à des entreprises cotée au premier marché.

Alors ce qu’ on peut penser de l’ état des subcultures c’ est qu’ elles survivent avec l’ élégance d’ une mauvaise herbe, du genre de celle qui sont matures à cinq mois et libère plus d’ oxygène que les tractopelles de l’ industrie et leur parterres de ronds-points.

Quand on regarde les réseaux sociaux, on voit tout le monde dans une attitude anticapitaliste et complaisante, mais que se passe-t-il réellement ? En tant qu’artiste, comment évaluez-vous ces extensions médiatiques qui nous sont présentées alors que « l’humanité » gémit de douleur dans la captivité des puissances impérialistes supranationales ?

Les populations sont sans défense devant des industriels, des banquiers, des militaires, des administrations et le contrôle inédit des GAFAM qui permettent de faire tourner le cirque. Mauvaise nouvelle, le monde a été kidnappé. Les medias sociaux sont des jeux vidéos dangereux, bien plus dangereux que le plus dégueulasse des FPS ou on pourrait torturer des petits chats au fer à souder. On attend Insta Kids avec une impatience à peine dissimulée. Victime de sa construction neurologique, le sapiens sapiens peut supporter sa vie vide de sens si il peut s’ en rêver une autre plus glamour sur Instagram.Echange paillettes virtuelles contre acceptation de soi même. Ca doit embaucher sec en psychiatrie en ce moment non ?

Quatre entreprises (Twitter, Youtube, Instagram, Facebook) dominent le monde ; Si nous considérons la civilisation comme un processus qui progresse jusqu’à sa perte, que pensez-vous que la jeunesse actuelle et l’humanité sont en train de perdre ? Suis-je trop pessimiste, corrigez-moi si je le suis.

Au contraire, je te trouve même plutôt optimiste. Les populations vont perdre progressivement et par à-coups leurs libertés jusqu’ à l’ asservissement total car elles acceptent massivement (car suggérées en permanence et de plus en plus efficacement) de troquer leurs libertés contre du confort. Ce troc est rendu ludique, donc en quelque sorte distrayant (crédit social, évaluation permanente dans les écoles, permis à …,media sociaux et followers etc … ) et donc accepté sans mouvement sociaux massifs. On nous fourgue l’ objet de notre asservissement en nous ventant libertés et facilités (encore de la suggestion). Par exemple aujourd’ hui ne pas posséder de smartphone revient a accuser un déficit de connectivité aux autres, un handicap social. Ne pas posséder de smartphone est aussi un handicap lorsqu’ il faut présenter des QR codes à la chaine. Il faut se soumettre au geste de dégainer le smartphone sinon le prix à payer sera l’ inconfort d’ une exclusion d’ abord moindre et qui deviendra invivable.

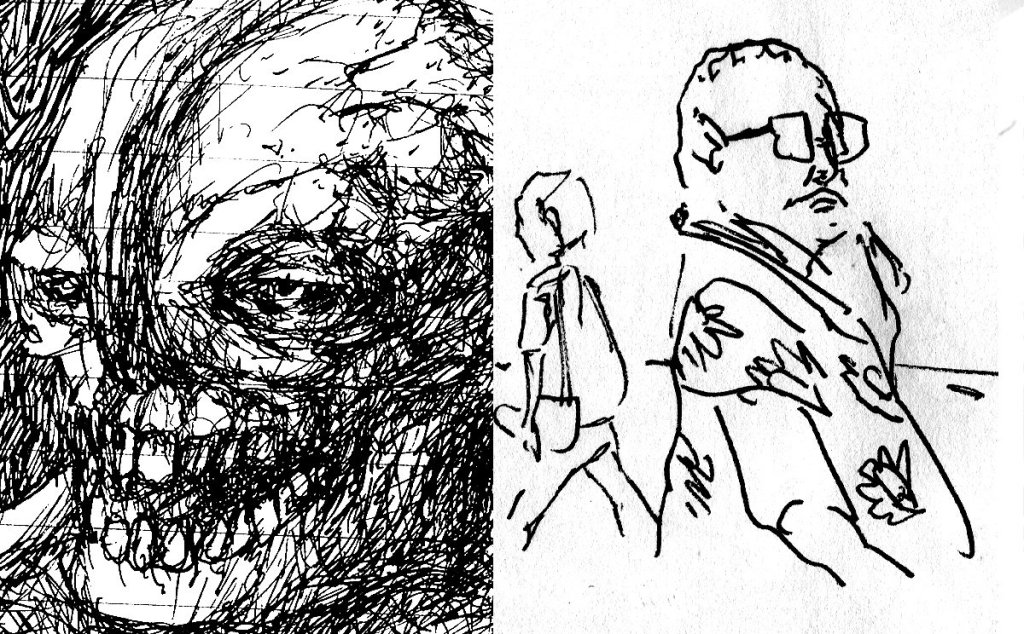

J’ ai dessiné nombreuses personnes dans la rue cet été. Beaucoup avaient des smartphones, une sur deux, à la main ou nà l’ oreille … Lorsqu’ elles le regardent elles sont toutes les sourcils plus ou moins froncés et ont l’ air éberluées lorsqu qu’ elles relèvent la tête et se sortent la gueule de la matrice LCD. Ce n’ est pas drôle de dessiner ces gens, les mêmes poses, les mêmes trognes mollement accaparées, mais en même temps si moi aussi j’ étais happé par un téléphone je ne pourrais pas les dessiner. Comme eux qui ne me voient pas, je ne les verrai pas non plus et il ne se passerait rien d’ autre que le croisement de plusieurs corps en mouvement enregistrés par des caméra 360° à tous les coins de rue pour seuls témoins. Zéro conscience les uns des autres. Les zombies m’ ont toujours fascinés et lorsque je regarde cette population avec un regard curieux semblable, l’ humanité s’ ensevellissant elle même dans une matrice totalitaire parait être un spectacle grotesque qui ne manquerait pas de pépitos s’ il n’était pas aussi tragique. Le spectacle “des sidérés” même s’ il ne m’ inspire guère me fascine.

En tant qu’artiste, comment évaluez-vous la période à venir et le “Great Reset” ? Êtes-vous mondialiste ou nationaliste, de quel domaine vous sentez-vous le plus proche ?

Je suis une personne qui regarde le cirque du pouvoir devenir dingue et les populations du monde écrasées à tous les niveaux par une oligarchie discrète dans ses agissements et disposant de moyens de contrôles des masses inédits dans l’ histoire de l’ humanité. La position nationaliste est elle encore viable lorsque les nations ne sont plus que des parts de marché divisées par cette oligarchie?

Que voudriez-vous dire sur le fait que Banksy et des artistes similaires, qui ont développé des critiques politiques radicales du siècle avec leurs œuvres, poursuivent également leur carrière avec les valeurs bourgeoises auxquelles ils s’opposent et avec de riches collectionneurs ?

A mon sens Banksy n’ est pas un artiste mais un communicant habile doublé d’ un piètre graphiste. Je laisse la parole à ses sponsors et aux trépannés du bulbe qui voient en lui une sorte de demi dieu de la suverssion pour parler de son book a défaut de parler d’ une oeuvre.

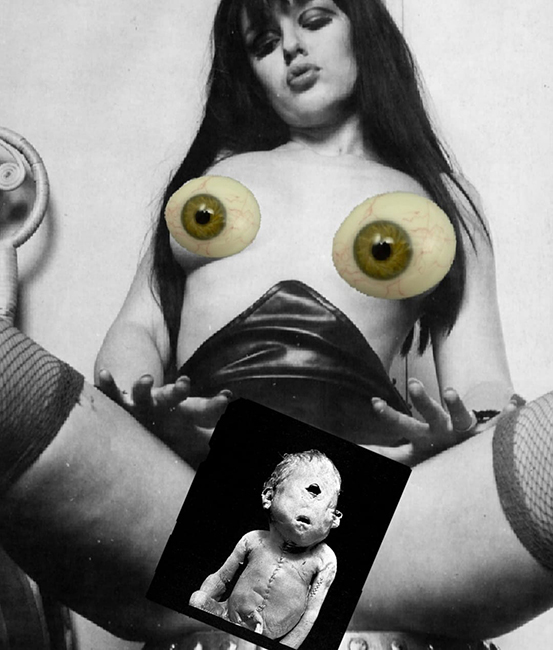

“Le Dernier Cri”, c’est d’abord une aventure artistique lancée par un artiste-punk phocéen. Pakito Bolino. Aux confins de l’art brut, du fanzine (ces petits journaux artisanaux alternatifs épris de rock, de bande dessinée, de SF…) il est l’un des fers de lance internationaux de ce mouvement rebelle qui a tenu à se libérer du marketing, en favorisant et décuplant la créativité de bon nombre d’artistes “underground”, pour beaucoup fans de métal et musiques extrêmes.

Vous souhaitez parler de l’exposition ‘Call From the Grave’ qui se tient à La Pop Gallery ? Cela ressemble à une exposition impressionnante et fantastique qui réunit les grands noms de la culture Grafzine, je me demande si l’événement n’a pas été un peu éclipsé par la pandémie ?

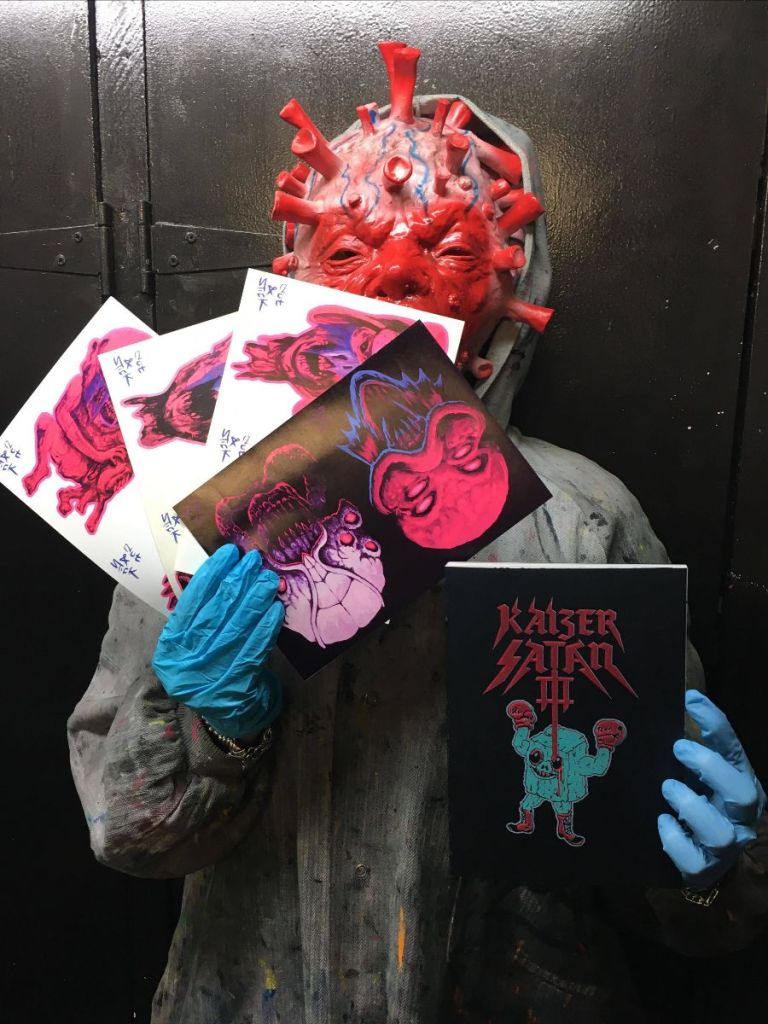

C’ est très flatteur, je suis sûr que Sam Rictus et Jurictus qui y ont participé auront une érection telle en lisant tes mots qu’ espérons qu’ elle ne leur soit pas fatale. Andy Bolus et Zven Balslev ont aussi exposé des peintures, dessins et collages. Bien sûr l’ exposition fut rendue difficiles par les règles arbitraires sans cesse changeantes de notre gouvernement fantoche mais ce fut l’ occasion de rencontrer Pascal Saumade, curateur au Musée International des Arts Modestes et qui tient la Pop Galerie. Il se définit non pas comme un collectionneur (au sens de “qui voudrait tout” comme il le dit) mais un amateur de pièces singulières. Je m’ arrêterai vite ici sinon je me perdrais sur la rivière étoilée du souvenir : l’ alerte à la bombe en gare de Sète; le couvre feu déclaré à Montpellier qui empêche les habitants de venir jusqu’ à Sète, l’ imitation sonore du chanteur de Pantera par Sam Rictus avant le premier café … Le mime de la copulation du diable de Tazmanie par Judex qui nous avait rejoint et les truculents récits liégeois de Cha Kinon qui ont pour héros des sacs de sport, des étrons et des belges …

“A la Pop Galerie de Pascal Saumade, une rencontre du troisième type”

“La preuvre à travers le panel d’œuvres, pour la plupart dessinées à l’encre de chine, qui ornent les cimaises de la Pop Galerie. Elles sont signées Jurictus, Sam Rictus, Zven Balslev et Dave 2000. El elles envoient… grave.”

Citations d’Marc Caillaud

mcaillaud@midilibre.com

Comment trouvez-vous Zven Balslev et Cult Pump, êtes-vous intéressé par son travail ? Il semble très bien garder l’esprit Underground Comix vivant à Copenhague.

C’ est un des dessinateurs les plus drôle et les plus poétique de notre époque. Le Docteur Good a rendu son energy drink par le nez en tournant les pages de son livre YAMA HAHA . Tous les dessins se composent de figures qui évoquent plus qu’ elles explicitent, et quand elle le font on se demande bien des pourquoi ? Des mais ? Bref, on s’invente une histoire contrairement aux comics qui nous en raconte une. On se marre de la naiveté décidée de ces compos en forme de mini poèmes absurdes, énigmatiques comme des figures de tarots sous LSD. Ses dessins me renvoient à une enfance intérieure, de jeu, de décodage, de figurines en plastiques sorties des tirettes mystérieuses de fêtes foraines. C’ est généreux, sans complexe, faussement évident et enfantin, comme tout ce qui est génial.

For Zven Balslev & Andy Bolus LDC Editions:

zven-balslev > andy-bolus

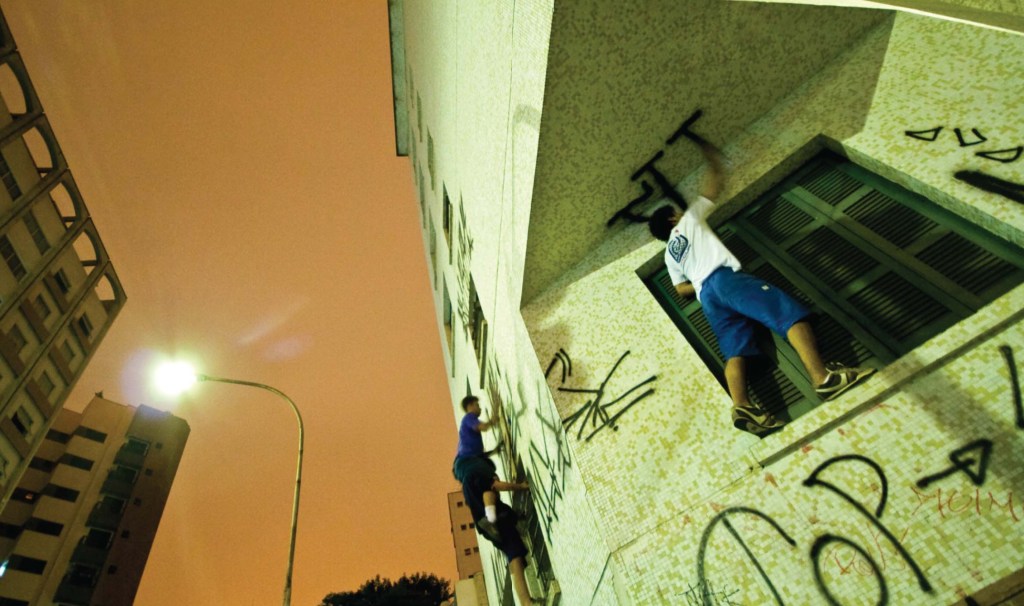

Qu’as-tu fait depuis ‘Call From the Grave’, tu sembles être sérieusement dans l’aquarelle, l’acrylique, les dessins et tu n’hésites pas à porter l’aventure aux graffitis ; en même temps, compte tenu du Kaizer Satan 3 sorti de LDC, nous dirions que vous êtes dans une période très productive où vous avez beaucoup développé votre art.

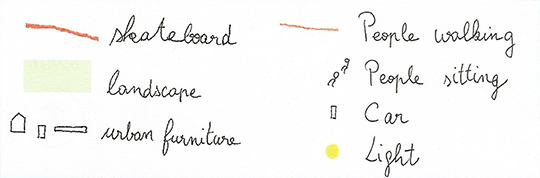

Dans le parc d’ attractions qui me sert d’ esprit et d’ agenda j’ ai mis en place plusieurs manèges. Les aquarelles de mes carnets sont la résultante de mes errance dans la ville de Marseille ou ailleurs. L’ aquarelle est une technique fabuleuse à bien des égards. Elle est très nomade, une boite de couleurs de la taille d’ un paquet de cigarettes, un carnet , un pinceau à réserve et en route pour l’ aventure. J’ observe dans la rue, dessine parfois d’ après nature pour capturer des formes, des rythmes. Me sert globalement de l’ ambiance urbaine pour dessiner ce qui me passe par la tête durant ces immersions. Ca a pour effet de radicalement changer mon rapport à la ville et de rendre ludique la réalité sordide des zombies ultra-connectés, des arbress coupés pour être remplacés par des sucettes publicitaires automatisées etc … L’ épouvante normale devient un jeu et ce jeu m’ appartient.

“Un château perpétuel” est une des attraction phare de mon esprit. Il s’ agit d’ une méta-peinture sans limite de bord ou de format composée de grands papiers peints à l’ acrylique. Chaque élément étant indépendant des autres mais fonctionnant dans un tout. Un château perpétuel n’ a pas non plus de nombre d’ éléments définis. Ainsi un peintre se lève le matin et si il se trouve désoeuvré après sa deuxième cafetière il n’ a qu’ à se dire à lui même “un peintre va perpétuer un château perpétuel”. “Un château …” n’ est donc pas un Work in progress comme on dit dans la société globale car un WIP a un début et une fin mais une peinture sans fin si ce n’ est la mort du peintre ou la cessation de sa pratique. Cette idée de peinture sans fin, sans bords et sans cadre m’ est venue d’ un ras le bol des expositions montrant des formats A5/A6 diposés orthogonalement dans des cadres Ikea et parfois même avec le sur-cadre d’ une Marie-Louise. Je trouve à titre tout à fait personnel indigne d’ artistes qui se réclament d’ une expression brute, sans tabou de se fourvoyer avec ce genre d’ accrochage standardisé. Je veux montrer de la peinture brute, sans fards, sans ce dispositif de mise en exergue ridicule soumis aux codes des galeries. De la peinture qui dit au spectateur “regarde, je ne suis qu’ un bout de papier peint qui est beau en lui même et par lui même”. Cette nudité dans la scénographie permet aussi au spectateur grâce aux relatifs grands formats de s’ immerger dans une oeuvre qui sans apparats semble alors accessible dans le sens d’ un “moi aussi je peux le faire, ce n’ est que du papier, de la peinture, des brosses, le coeur, l’ esprit et la main” au contraire des cadres et sur-cadres qui signifient “c’ est encadré, c’ est précieux, c’ est expert, voila ce que tu dois admirer et ne pourras jamais faire pauvre spectateur”.

J’ imagine en ce moment un nouveau manège urbain qui s’ intitulera “7074L GLO34L” et consistera à coller des peintures ironiques qui nieront ou détourneront les affiches de politiciens ou d’ annonceurs qui envahissent les panneaux d’ expression dites “libres”.

Pour finir et en prévision de l’hiver il me reste à terminer une animation 3D noir et blanc dans la lignée de “5 automates” et basée sur le roman “Le maître et Marguerite” de Mikhaïl Boulgakov.

Qu’aimeriez-vous dire à propos de l’exposition NAROK, je pense que cet événement était plus une exposition essayant de capturer l’atmosphère Asian Extreme. Comment trouvez-vous ces idées créatives de Pakito ; il synthétise les mouvements graphiques et d’illustration modernes avec des écoles excentriques qui ont germé dans des contrées lointaines (comme le japonais Heta-Uma), et il arrive toujours à nous surprendre ; Selon vous, qu’est-ce qui le rend si créatif comme ça, pensez-vous qu’il a un vrai côté malveillant et négatif ? Ou ne montre-t-il que cette facette de lui-même dans ses œuvres artistiques ?

Je pense que Pakito n’ a pas besoin de chercher d’ idées, les intermittents de l’ art “cherchent”, Pakito “trouve” sur son chemin artistique car pour lui l’ intermittence de l’ artiste n’ existe pas. Quand il n’ est pas à imprimer pour le DC, il est en vadrouille pour on ne sait quelle intervention, rencontre, ou salon d’ édition. Hors des heures ou il n’ est pas pris dans le courant des activités du DC il dessine quotidiennement ce dont il parle comme d’ un défouloir. Ce qui le rend si créatif est d’ avoir dédié sa vie à l’ art sans calcul, sans carrière et dans ce que l’ art a de plus humain, énergique, partageur, inventif, et résistant au formatage global. Avec Odile de La Platine (chargée des impressions en offset pour le Dernier cri et à la tête d’ une des dernières imprimerie artisanales de Marseille) le Dernier cri possède ses propres moyens de production autonomes ce qui est aussi une pièce maitresse de la créativité car ces moyens permettent la liberté, autant dans le propos que dans des choix techniques (nombre de couleurs, formats, pages si il s’ agit de livres).

Il y a quelques années, grâce à Mavado Charon, il m’a envoyé le livre Graphzine Graphzone. Comme le livre est en français, je n’ai pas pu tout lire, mais il est évident que des études sérieuses ont été faites en France depuis les années 70, quand on regarde les artistes de l’ancienne génération comme Pascal Doury, Bruno Richard, Olivia Clavel , et des magazines de contre-culture comme Elles Sont de Sortie et Bazooka. En tant que l’un des artistes phares de ce domaine aujourd’hui, de quelle école vous sentez-vous plus proche ? Et de combien de générations peut-on parler ?

Je me trouve bien mal placé pour en parler car avant le début des années 90 je vivais dans un bled situé dans les montagnes vosgienne en fRance et ce que je connaissais de l’ underground se limitait à la musique, à la scène démo et au piratage informatique. Je ne connaissais presque rien aux sous mondes de l’ art si ce n’ est des jaquettes photocopiées de démos de metal ou de punk et des cracktros des jeux vidéos piratés avec leurs lettrage délirants. C’ était déjà très fort, d’ autant plus que ces choses difficiles à se procurer révelaient à mes oreilles et mes yeux l’ existence d’ un monde d’ autonomie et de liberté jusqu’ alors complètement absent de ma réalité colonisée par la télévision et les livres sur les vainqueurs (souvent post-mortem) de l’ histoire de l’ art. Lorsque je rencontrais le travail des artistes dont tu parles plus haut j’ avais déjà une culture sub-graphique construite sur ma pratique et aussi les rencontres faites à Strasbourg, notamment avec Vida Loco qui préparait alors son premier livre “8Pussy” qu’ il serigraphiait lui même. Pour en revenir aux artistes que tu évoques, même si leur travail n’ a pas eu d’ influence sur moi je sentais cette vivacité, cette volonté libertaire et ce refus des limites de l’ industrie. Tout ça m’ inspirait énormément et cette même énergie continue à porter ma pratique et définir mes choix actuellement.

Quand on regarde Stéphane Blanquet et l’UDA, on voit une attitude surréaliste, élitiste qui vient surtout de l’école de Roland Topor ; Bien qu’il y ait aussi des artistes très talentueux chez LDC, c’est comme une équipe qui travaille plutôt dans une ambiance rock’n roll. Pakito a-t-il une attitude ou une position contre l’art élitiste dans un sens réel, dans un contexte idéologique, ou est-ce que tout le processus fonctionne comme ça à cause de son style de vie ou de celui des artistes collaborateurs ?

UDA et LDC ne proposent pas la même chose. UDA permet à des artistes underground de voir leurs oeuvres diffusées par exemple dans “La tranchée racine”, un hebdomadaire au format d’ un quotidien d’ information imprimé en quadrichromie par une entreprise en sous-traitance. Les moyens de productions sont ici ceux de n’ importe quel éditeur mainstream en somme. UDA organise aussi des expositions collectives dans des lieux prestigieux tels que la Halle Saint Pierre à Paris tournant autour de la personnalité de Stéphane Blanquet, CF : “Stéphane Blanquet et ses invités” à Aix en Provence.

LDC quant-à lui propose à des artistes de venir dans son atelier avec des originaux, de les scanner, les mettre en couleur si nécessaire, de choisir un papier, un format, des encres. Le DC permet aussi d’ apprendre à imprimer en sérigraphie si les artistes ne savent pas le faire eux même et pour finir de monter une exposition dans l’ espace dédié pour célébrer la sortie de leur livre. Tout comme UDA, les artistes se voient proposé de participer à des expositions collectives mais qui ne tournent pas autour du personnage d’ un leader mais de la structure elle même par exemple “Mondo DC” ou d’ une idée générique – “Heta Huma” ou “Narok”. De plus chaque année a lieu le festival de micro-édition Vendetta qui fait se converger de nombreux artistes, éditeurs et qui est organisé par le DC.

On a donc deux éditeurs/producteurs d’ artistes underground et deux moyens de production fondamentalement différents, l’ un va dans le sens d’ une production assistée relativement massive et impressionnante en terme de format, d’ exposition dans des lieux prestigieux, de technique quadri et de nombre de multiples permis par la sous-traitance. L’ autre avance dans le sens d’une auto suffisance de production, de liberté de choix d’ édition, de qualité et de savoir faire artisanal, d’ élévation et d’ émulsion artistique. Bon nombre de structures tendent vers cette autonomie salvatrice et cette liberté courageuse initiée et perpétuée par LDC, comme Epox et Botox, Le Garage Hell, Cult Pump, Meconium, Turbo Format, Papier Gachette etc … Ils sont légion car l’ intégrité fait des enfants.

Je demande cela parce que, cela me rend triste que de si bons artistes comme vous soient coincés uniquement dans le domaine de la bande dessinée. Quand on regarde l’art contemporain et les biennales exposées aujourd’hui dans le monde, on voit bien la crasse bourgeoise. Et je pense que vous avez essayé de peindre cette aliénation synthétique et cette dévaluation dans votre tournée d’exposition d’animation 3D que vous avez récemment publiée.

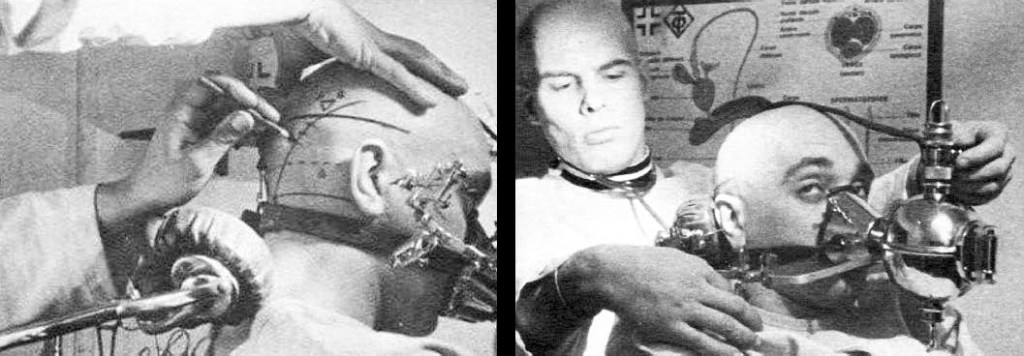

Cette animation dont tu parles montre une exposition virtuelle dans un futur assez proche et qui me met en scène (bien que j’ y sois invisible) en tant qu’ artiste inutile et donc à réhabiliter socialement Dans cette courte fiction animée les moyens de réhabilitation font l’objet d’ un vote du public – le travail forcé dans les mines de siliciums, la castration au laser, la lobotomie etc … exactement comme on vote pour le départ d’ un participant à une émission de télé-réalité. La visite virtuelle est faite par un guide, lui même en cours de réhabilitation et sérieusement alcoolique, chargé de montrer au public les oeuvres dégénérées d’ un artiste nuisible au bon fonctionnement sociétal selon le pouvoir en place. Je vois ce film comme une à peine parodie gentillette de ce que l’ oligarchie globalisée et son armada numérique nous préparent en termes de surveillance, de contrôle, d’ uniformisation, de formatage des esprits et bien entendu de violence.

Quant aux artistes conceptuels du milieu dit de “l’art contemporain” que tu évoques je vais faire court à leur sujet. A mon sens un artiste plastique est un pantin méprisable si il n’ est pas capable une fois jeté nu dans une cellule de tapisser de graffitis les murs de sa prison et de les transformer en une oeuvre merveilleuse à faire Michel Ange se lever de sa tombe pour aller repeindre les plafonds de la chapelle Sixtine avec l’ enthousiasme d’ une jeunesse retrouvée. Partant de ce postulat, ces fifrelets, ces remplisseurs de dossiers de demande de subventions, ces branles-verbe ne m’ intéressent guère, tu t’ en doutes et ce qu’ ils pourraient penser de mes activités artistiques n’ a pas la moindre importance en comparaison du rire d’ un enfant qui me regarde dessiner un “père noël qui fait caca”.

Merci beaucoup Dave d’avoir pris le temps de parler, et merci de partager les dernières nouvelles de France ; nous suivons votre travail avec enthousiasme, au revoir pour l’instant, mon ami, prenez soin de vous !

Bon courage mon ami prends soin de toi !

Pour suivre les dernières évolutions de l’artiste :

> protopronx.free.fr

> pitpool.free.fr

Pour une conversation plus ancienne avec l’artiste :

Dave 2000: Pas un Artiste un Ninja (2016)