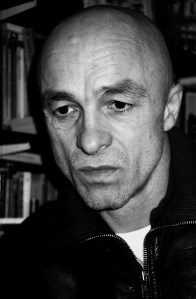

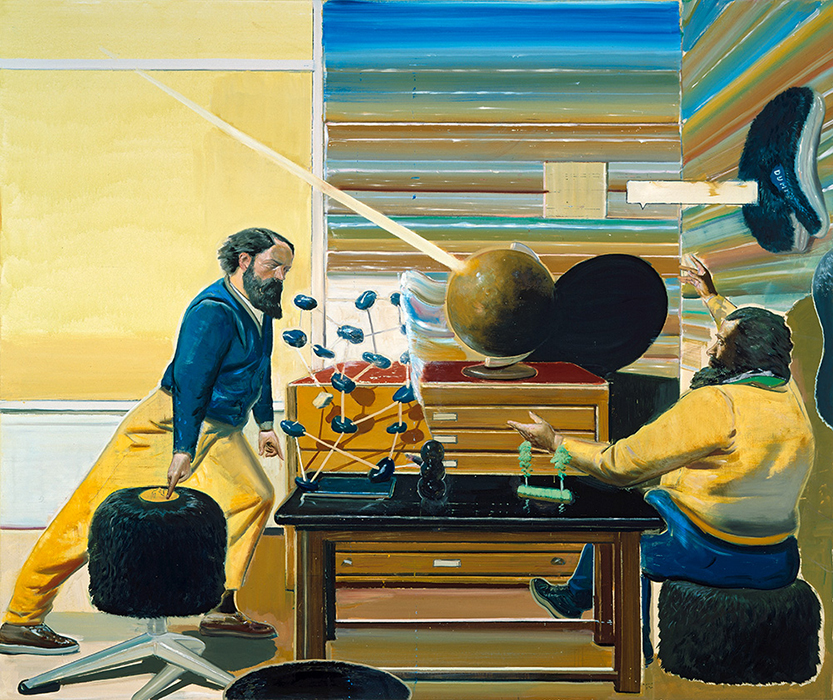

Neo Rauch, eserlerinde kendi kişisel tarihinin, endüstriyel yabancılaşmanın politikasıyla olan kesişme noktalarının derinlerine iner. Resimleri toplumsal gerçekçilik etkilerini yansıtır, her ne kadar kendini bir sürrealist olarak tanımlamasa da çalışmaları Rauch’un Sürrealist Giorgio de Chirico ve René Magritte’e çok şey borçlu olduğunu gösterir. Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig’de okuyan Rauch, Almanya’da Leipzig yakınlarındaki Markkleeberg’de yaşıyor ve New Leipzig School’da öğretmenlik yapıyor. Sanatçı aynı zamanda Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/ Berlin ve David Zwirner, New York tarafından temsil edilmektedir.

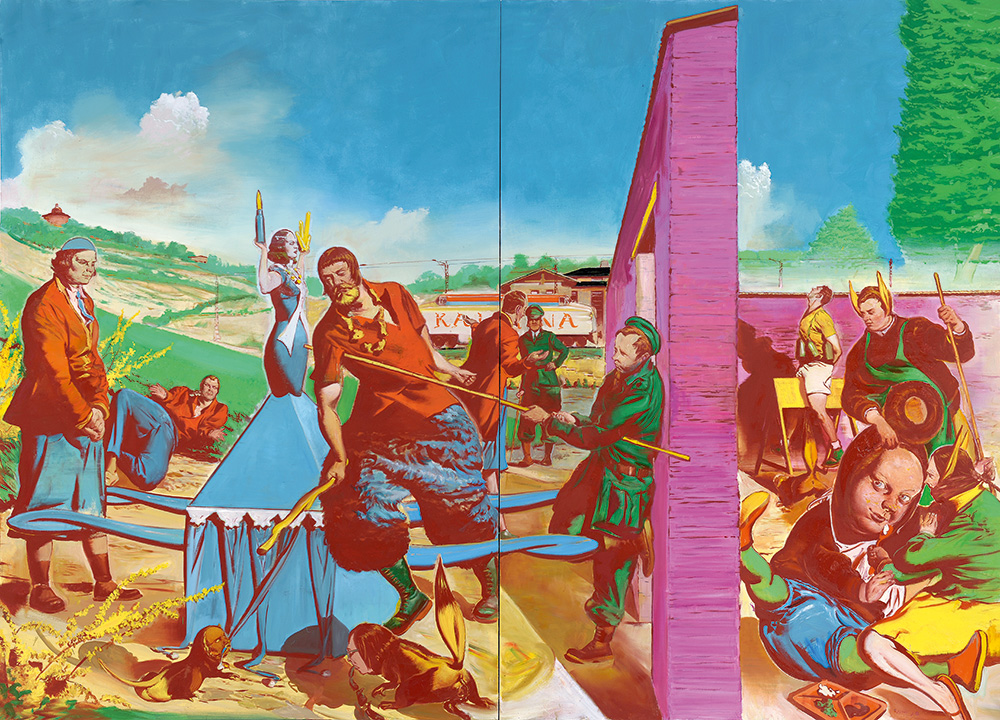

Bir sanat tarihçisi olan Charlotte Mullins, açıklamasında Rauch’un resimlerinin bir hikaye anlatacakmış izlenimi uyandırdığını fakat yakından incelendiğinde izleyiciye sadece bilmeceler sunduğunu ifade eder; mimari öğeler miyadını doldurmuş, geçmişteki üniformalı adamlar yüzyılları aşarak insanları sindirir, nedeni açık olmayan mücadeleler gelişir, tarzlar geçici heveslerle değişir.

Resimlerinde stilizasyon, önermeler ve sonsuzluk dikkat çekicidir.

“Resmetme sürecini son derece doğal bir biçimde dünyayı tanıma yöntemi olarak görüyorum, neredeyse nefes almak kadar doğal. Görünürde neredeyse kasıtsız şekilde gelişiyor. Bu ağırlıklı olarak konsantre bir akış süreciyle sınırlı. Bilinçli olarak bu yaklaşımdaki masumiyeti baltalayabilecek katalitik etkiler üzerinde düşünüp taşınmaktan kaçınıyorum çünkü hatlarda örnek yoluyla belli bir dereceye kadar netlik göstermek istiyorum. Kendimi zaman nehrinde bir tür sığamsal bir filtre olarak görüyorum…”

Rauch, New Leipzig School’un bir parçası olarak görülmekte ve çalışmaları Komünizmin Toplumsal Gerçekçiliğine tabi bir tarzda nitelendirilmektedir. Özellikle Amerikalı eleştirmenler onun çağdaş tarzındaki Post Komünist Sürrealizmi görmeyi tercih etmektedirler. Fakat Rauch herkesten daha çok Doğu-Batı ressamı olarak tanınmaktadır. Rauch, hem Varşova Anlaşması hem de Batı dünyasının modern mitlerini bir araya getirir. Figürleri Amerikan Çizgi Roman-estetiğini komünizmin Toplumsal Gerçekçiliği ile buluştuğu bir planda resmedilmiştir. Rauch, sanatsal yayın Texte zur Kunst’da yeni-Alman muhafazakarlığı akımına örnek gösterilmiştir.

Organizatörlerinden biri Roberta Smith (New York Times yazarı) “Soğuktan gelen ressam”la ilgili makalesiyle Rauch’un eserlerinin Amerika’da büyük coşkuyla karşılanmasını sağladı. 2007’de Rauch, New York’taki Metropolitan Müzesi’nin Modern Sanat kanadının ek katında sergisi için özel bir seri çalışma yapmıştır. Bu özel serginin adı “Para”. Rauch bunu Para’nın zihninde oluşturduğu çağrışımlardan aldığı keyifle açıklar ve “Para” çalışmalarında özel bir niyeti olmadığını ama herhangi birinde herhangi bir anlamı uyandırabileceklerini söyler.

“Metropolitan sergisi ile ilk anlaştığımızda müze atmosferi ile ilgili bir çalışma şekli düşündüm. Ama hemen farkettim ki stüdyomdaki “ Witches Circle’dan imgeler”le, tamamen tematik bir şekilde meydana çıkan şeylerden daha çok ilgileniyordum. Onları “imgeler” olarak adlandırmak karakterimi yansıtıyor – ilhamdan üstünler ve bilişsel kararlar harekete geçerken içsel imgelerin ortaya çıktığı anlardan fırlıyorlar. Bu şekilde keşfettiğim herşeyi kabul etmekten başka şansım yok.”

“Para” çalışmaları:

- Jagdzimmer (Avı’nın odası), 2007

- Vater (Baba), 2007

- Die Fuge (Füg/Boşluk), 2007

- Warten auf die Barbaren (Barbarları Beklerken), 2007

- Para, 2007

- Paranoia, 2007

- Goldgrube (Altın Madeni), 2007

- Vorort (Banliyö), 2007

- Der nächste Zug (Sıradaki Hamle/Sıradaki Çizim), 2007

- Die Flamme (Alev), 2007

“Para” için üretilen eserler üç öğeyle karakterize edilir; prekomünist kentseldüşüncelilik, komünist Toplumsal Gerçekçilik ve idealize edilmiş bir kırsal. Diğer yandan paranormal, paradoks ya da paranoya gibi kelimelerle bağlantılı çağrışımlar yapan bir örnek. Sistem bağlantısı içinde okunabilir, örneğin Paranoia gibi bir resim hermetik bir odada bilişsel teorileri yansıtabilir.

Rauch’un içinde doğduğu şehir Leipzig, Leipzig Ticaret Fuarı sayesinde tarihi bir ticaret şehri olarak bilinir. Die Wende’ye (Değişim) kadar varan popüler direnişin merkezi olan Leipzig gibi bir ticaret şehrinde kentsel düşüncelilik ayrıca kendini komünizm içinde ifade eder. Rauch, Doğu Almanya’da komünizm tarafından ezilmiş prekomünist sivil toplum hayatının karakterleri ve imgelerini kullanır. İdeolojilerin bu yıkıcı güçleri belki de Rauch’un kendi eserlerini, yıkıldığı sanılan kentsel burjuvazi düşüncesinin şekillendirdiği haliyle kültürel görecelik hatrına güçlü cümlerlerle açıklamayı reddetme nedenidir.

Mechanic of Dreams

Interview by David Molesky, Juxtapoz mag. 2019

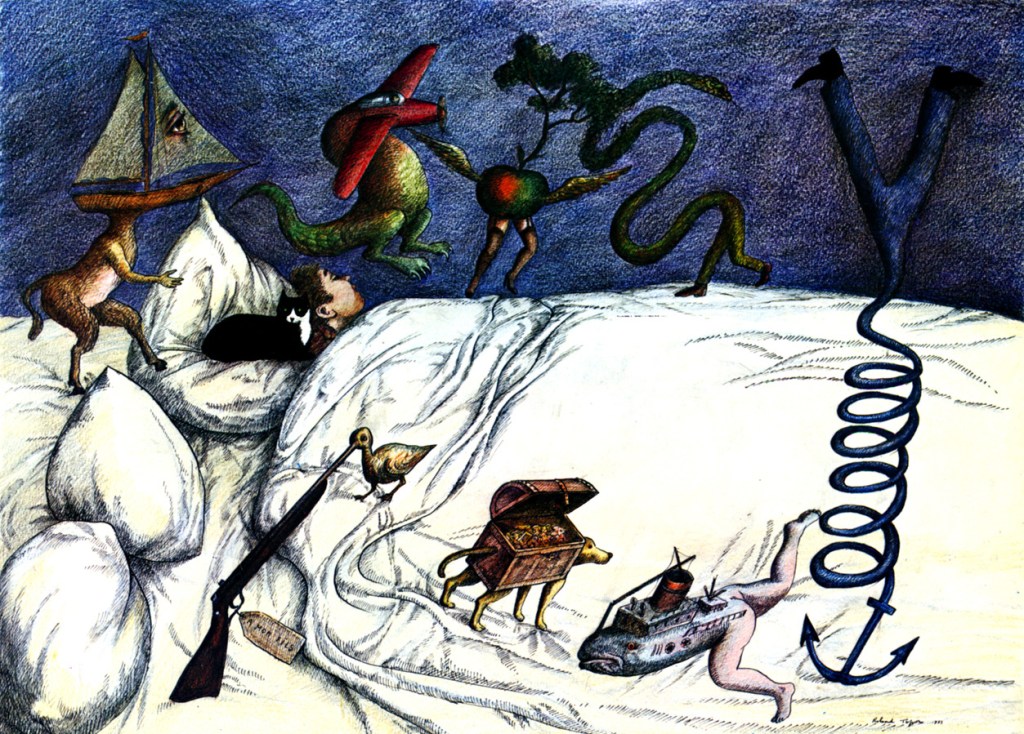

Neo Rauch once expanded a variation on Descartes famous meditation and said, “I dream therefore I am.” In an era where thinking is often outsourced to computers, dreaming is an activity intrinsically human. Dreams can magically leave us feeling simultaneously connected to universes of time—present, past, and future.

Neo Rauch’s work stands before us like a portal that links our era with all of its Postmodern confusion back to a time when fairy tales served as plausible short stories. With feet firmly rooted in his native Saxony, Rauch engages an ethereal undercurrent of symbol and storytelling.

Neo Rauch has often said that his overall mission is to re-enchant the world and take off where the Romantics left off. In reading many of his previous interviews, one gets the sense that Rauch engages a spectrum of pre-Enlightenment and Romantic occult wisdom. He mentions the Akasha, bursts of pantheism, time continuum, and Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea as representing the awareness of one’s placement within a grand design.

Allowing hypnagogic visions to guide his foray into new compositions, Rauch works mostly in stream-of-consciousness with no preliminary drawing. Flowing from his trance state, the painting takes on a life of its own. Rauch spoon-feeds his creature-like creations from brushes held by large, clumsy-looking gardening gloves with paint he mixes on the floor in containers before his canvases. He keeps a schedule like a factory worker: 9 AM–7 PM, five days a week, working on three to five large canvases at a time. On the weekend he lets the paint dry, takes a break from the studio, and spends time with his family working in his garden.

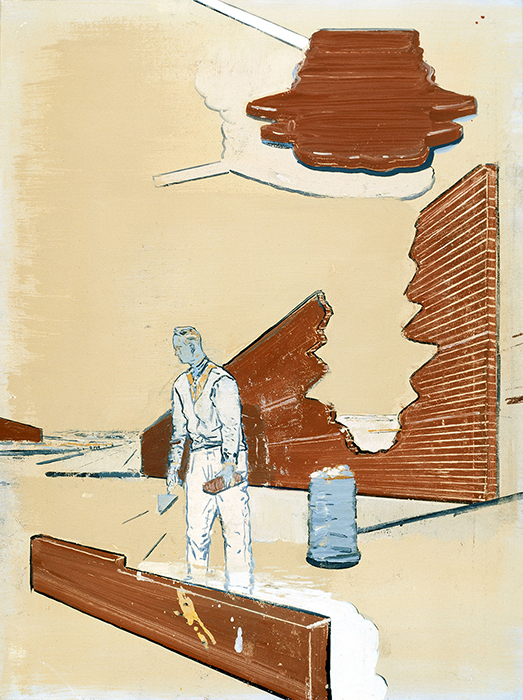

For three decades, Rauch’s efforts have resulted in his own distinct world populated by humans and humanoid subjects that he refers to as his paintings’ personnel. These characters interact in an atmospheric space that challenges us with scale change, perspective shifts, and intense passages of color. The integration of historical architecture and dress, with the special effects of science fiction, spans the viewpoint across different eras of human history.

Neo Rauch was raised by his grandparents in Aschersleben after a train accident put an early end to the lives of his young parents, who at 19 and 21, were both still art students. Rauch would later attend his parents’ alma mater, Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig (Leipzig Academy of Visual Arts), receiving an MFA and becoming a professor there from 2005–2009. Having remained in Leipzig his entire adult life, Rauch feels a deep connection to the intellectual and creative legacy of the region’s terroir. Since the early ’90s, Rauch has made a top floor studio space in an old cotton mill the epicenter of his creative activities, with his wife, casein painter Rosa Loy, working in another studio just across the hall.

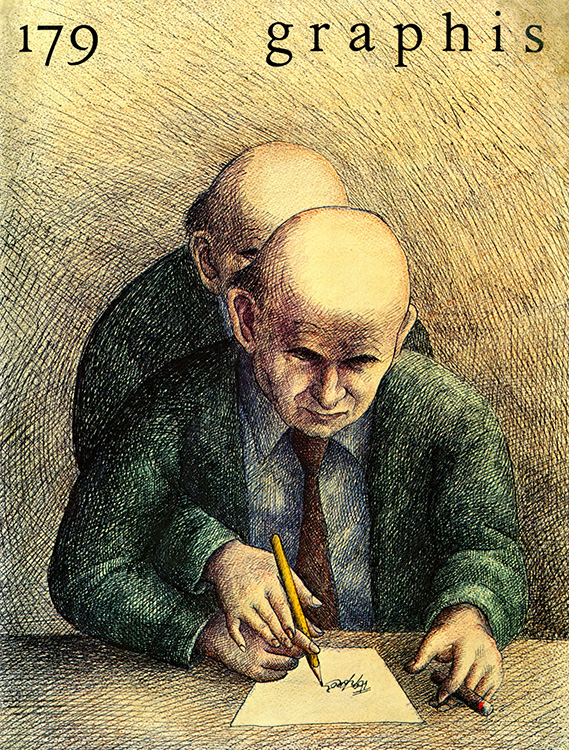

Twenty-five years ago, Rauch had his first solo exhibition with Eigen+Art, which is still his principal gallery in Europe. At the turn of the millennium, he was picked up by New York gallerist David Zwirner, followed by a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007. When Rauch turned 50 in 2018, he was given a retrospective exhibition, titled Dromos, that filled all four floors of the Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle, Netherlands. This past summer, Rauch and Loy designed the costume and set for the Bayreuth Festival’s production of Wagner’s Lohengrin, which will continue to be staged for the next three summer festivals. Reopening this April at The Drawing Center in Manhattan, an exhibition traveling from the Des Moines Art Center, will feature 170 drawings by Rauch on A4 standard paper.

Over the Holiday break, Rauch was able to squeeze in an interview with Juxtapoz as he prepares for a solo exhibition opening March 26, 2019 at David Zwirner’s new gallery space in Hong Kong. David Molesky fired off a set of questions hoping to gather insight into the mind and process of the most epic painter hailing from Eastern Germany. ––Juxtapoz

David Molesky: I felt so fortunate that I was able to see your exhibition, Dromos. Retrospectives are an unprecedented opportunity for an artist to reflect and to make comparisons between images. What was the takeaway realization upon seeing your work filling the Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle, Netherlands?

Neo Rauch: It was like a family reunion, a great homecoming with touching moments of reuniting and recognition. A few of the pictures I had not seen for a long time, and all—really all, even the older ones, somehow aged well.

Also, the interlocking of images from two decades does not seem abrupt or inorganic at any point; on the contrary, everything harmonizes in the most excellent way without giving up tension.

It is inevitable that an artist who has worked prolifically for decades will find some repetition and certain aspects that are continuous. Despite a stated resistance to analyzing your pictures, are there any patterns in your narratives which you cannot avoid noticing?

Certainly, there are recurrent patterns. Above all, probably the fact that the interactions of my characters are caught in a state of limbo; that they never really connect or even maintain eye contact. Also, I avoid, with very few exceptions, the eye contact between figures and viewer. I always perceive such stagings as indecent.

In addition, there may be props, such as the burning backpack or cannons, which appear directly or in modified form again and again. Architectural elements, such as factory chimneys and church towers, are also found again and again over the decades, as well as clouds of smoke! No smoke without fire.

It’s exciting that you recently translated your theater-scaled paintings into the third-dimension of opera. How has the opportunity to design costume and sets for Lohengrin affected your approach to painting? And how sensational that this has sparked a collaborative process with your wife Rosa Loy! I love that you stated, “It was easier than driving in the car together.” Will you collaborate on future projects?

This is not yet foreseeable; the impressions left by the stage design are still too fresh to serve as a mold for pictures. They have to cure first. The effect of the light in the room has, in any case, addressed the painter directly, and it remains to be seen how and if this experience is reflected on the canvases.

Yes, working with Rosa is indeed a great pleasure. She is very nimble—in the head and with the eyes—and thus, fills a fatal gap that gapes on my part. For the time being, there are no stage projects on the horizon, with the exception of our further work on Bayreuth Lohengrin.

I am looking forward to seeing your exhibition Neo Rauch: Aus dem Boden/From the Floor when it comes to The Drawing Center in Manhattan. How do you use drawing in your practice? I would imagine drawings, which are not preliminary, could be used as exercises to help you feel out various sensibilities, like what you’ve called “the moment prior to excess.” Ms. Loy must be helpful navigating these regards. She is an exceptional painter in her own right, and I’ve heard the only person you allow into your creative process?

As part of my work, the drawing is considered a kind of by-catch; she gets into the net, yet the hunt was meant for larger prey. These are, at best, finger exercises, which I complete in a trance-like state, and which take place in the run-up to a canvas project. However, they do not prepare them directly, but only charge the space between me and the canvas atmospherically. Yes, Rosa is actually the only person whose advice and help I ask for when needed. One should be picky and careful in this regard.

You’ve described that your initial motivation in beginning a composition comes from dreams or hypnagogic visions that can sometimes be as vague as a concept or a phrase. What techniques or rituals do you engage in to encourage yourself to remain in these kinds of mindstates?

I derive my pictures directly from dreams only in very rare cases. Rather, I try to simulate the mechanics of a dream event. That is, I go before the picture on the sloping path of free-flowing imagining. Gravity eventually brings things together, creating a common sound. The rational can assist at best. When she takes over the direction, propaganda or journalism arise.

I am very interested to know more about your view of universal processes and their relation to the collective unconscious. Could you direct me to concepts that might deepen my understanding of how paintings work to bring re-enchantment to the world?

If one agrees that painting penetrates into spaces in which concepts become blurred and words lose their competence, then one accepts the management of undercurrents that unfold their own magnetism.

Julien Green, for example, described very clearly how the perception of a ray of light falling on an armchair became the starting point of an entire novel. The creative person differs from someone acting creatively, in that they become the medium through which something wants to speak to us.

As your work is celebrated more and more, society will inevitably want to find a message in your enigmatic paintings. What might you hope can be gleaned through your life project as a painter?

If it were possible to help a few people to suspect that under the concrete of reality a life pulsates, which forms branched mycelia and suddenly comes to the surface in the form of a work of art, then much would have been gained.

Art is unpredictable and eludes appropriation; it is a phenomenon that amazes us and should awaken a certain reverence for the possibilities of the creative. It is a gift and a miracle, and thus, the absolute opposite of what political commissars and ideologues want to make of it.

Having spent your entire life based in Leipzig, the largest city in the German state of Saxony, I am particularly intrigued by your sense of pride for this region and your engagement with its rich history of intellectual and artistic pursuits. In researching for this interview, I learned that the composer Wagner and the philosopher Nietzsche hail from Saxony. Through one of your interviews I also discovered Novalis, the great Romantic writer was also from Saxony. What common point of inspiration might foster like-minded creatives from this region?

It should by no means go unnoticed that Max Beckmann was born in Leipzig, and that J.S. Bach worked in the city as Thomaskantor (the music director of an internationally known boys’ choir founded in Leipzig). The cultural humus on which one could found their workshop here is so dense and nutrient-rich. The connecting element that led to this condensation may be atmospheric. Climatic conditions conducive to creative activity could also play a role. I just do not know.

You are known internationally for your work as an individual artist, as well as for your position as a leading member of the New Leipzig School of painting. Tell me a little about how this community has supported each other and grown together. Has your role as the leading figure in this art community helped nurture your own work and sense of purpose?

The “New Leipzig School” is a term that emerged independently and outside of our consciousness as painting contemporaries. This label was pinned to us and did not appeal or seem fitting to everyone. Basically, it referred to the fact that in Leipzig, painting was still taught on a high figurative level, even though most “experts” in the early ’90s thought to abolish the utilization of brushes after 40,000 years. Painting was considered obsolete by these cretins, and those who nevertheless turned to it could be sure of their contempt and ignorance. In this respect, these years were a healing retreat, in the course of which it came to a thinning of the people, as only the real painter could resist the temptation of electronic cabinets and those of conceptualist seminars.

In any case, working in this blind spot was beneficial to my work, although the feeling of being marginalized was already gnawing at my pride. My first big personal exhibition with Judy Lybke at the gallery Eigen+Art in 1993 was a commercial flop, although the pictures were great! Only that at the time, the only people who saw it that way were Rosa, Judy, and me.

What will you be showing for your upcoming exhibition at David Zwirner in Hong Kong? What new developments have you explored in this new body of work, and are there any aspects of this work that have come about in consideration of the location?

There will be eight large (nearly 10’ x 9’) and seven small “handbag-sized” pictures. Whatever is new to them, new to my standards, that is, will only come to me much later. I am still too entangled in the sometimes agonizing development of these canvases to be able to attest to them a peculiarity. Also, the location of the presentation did not play a major role, yet rather an underlying one.

Neo Rauch’s Aus dem Boden / From the Floor will be on view at The Drawing Center, NYC, from April 12—July 28, 2019.

Resource: Juxtapoz magazine

Neo Rauch (born 18 April 1960, in Leipzig, East Germany); is a German artist whose paintings mine the intersection of his personal history with the politics of industrial alienation. His work reflects the influence of socialist realism, and owes a debt to Surrealists Giorgio de Chirico and René Magritte, although Rauch hesitates to align himself with surrealism. He studied at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig, and he lives in Markkleeberg near Leipzig, Germany and works as the principal artist of the New Leipzig School. The artist is represented by Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and David Zwirner, New York.

Rauch’s paintings suggest a narrative intent but, as art historian Charlotte Mullins explains, closer scrutiny immediately presents the viewer with enigmas: “Architectural elements peter out; men in uniform from throughout history intimidate men and women from other centuries; great struggles occur but their reason is never apparent; styles change at a whim.”

In painting “Characteristic, suggestion and eternity” are important marks of quality.

I view the process of painting as an extraordinarily natural form of discovering the world, almost natural as breathing. Outwardly it is almost entirely without intention. It is predominantly limited to the process of a concentrated flow. I am deliberately neglecting to contemplate all of the catalytic influences that would have the power to undermine the innocence of this approach because I would like to express a degree of clarity in these lines by way of example. I view myself as a kind of peristaltic filtration system in the river of time …

Rauch is considered to be part of the New Leipzig School and his works are characterized by a style that depends on the Social Realism of communism. Especially American critics prefer to recognize in his contemporary style a post communist Surrealism. But more than anyone Rauch is recognized as an East-West painter. Rauch merges the modern myths of both the Warsaw Pact and the Western world. His figures are portrayed in a landscape in which an American Comic-Aestheticism meets the Social Realism of communism. In the art publication Texte zur Kunst (Texts about Art, number 55), he was defined as an example for a new German neo-conservatism.

In the US, Roberta Smith, art critic for the New York Times, called attention to Rauch’s work in 2002 with an article about the “painter who came in from the cold.” In 2007, Rauch painted a series of works especially for a solo exhibition in the mezzanine of the modern art wing at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. This special exhibition was called “Para.” Rauch explains that he enjoys the associations the word “para” evokes in his own mind, and says that his works at “Para” have no particular intention, but that they could signify anything to anyone.

When I first agreed to do the Met exhibition, I thought about a way of working that would be about the nature of a museum. But straight away I realized that I was much more interested in those “visions from the Witches Circle” in my studio than I was in coming up with things in a purely thematic way. Calling them “visions” reflects my personality—they precede inspiration and spring from the moment when internal images appear at the prompting of intellectual decisions. I have no choice but to accept everything that I discover in this way.

Works for “Para”:

- Jagdzimmer (Hunter’s room), 2007

- Vater (Father), 2007

- Die Fuge (The Fugue/The Gap), 2007

- Warten auf die Barbaren (Waiting for the Barbarians), 2007

- Para, 2007

- Paranoia, 2007

- Goldgrube (Gold Mine), 2007

- Vorort (Suburb), 2007

- Der nächste Zug (The Next Move/The Next Draw), 2007

- Die Flamme (The Flame), 2007

The works created for “Para” are characterized by three elements: a pre-communist civic-mindedness, communist Social Realism, and an idealized countryside. On the other hand, it’s a prefix which evokes associations like para-normal, para-dox or para-noia.

It may be read in a system connection, for example a picture like Paranoia reflects the cognitions theory in a hermetic room.

Leipzig, Rauch’s city of birth, is known historically as a city of trade through its association with the Leipzig Trade Fair. This civic-mindedness of a trader’s city also expressed itself under communism where Leipzig was the center of popular resistance that led to Die Wende. Rauch uses characters and images of life of pre-communist civil society that was oppressed by communism in the GDR. The oppression of communism and the total control of civic life under the rule of communist ideology is one of the elements of Rauch’s work. The destructive powers of ideologies is perhaps the reason why Rauch refuses to interpret his own work as a powerful statement in favor of a cultural relativism that characterized the civic bourgeois thought that was destroyed.

Resouce: wikipedia

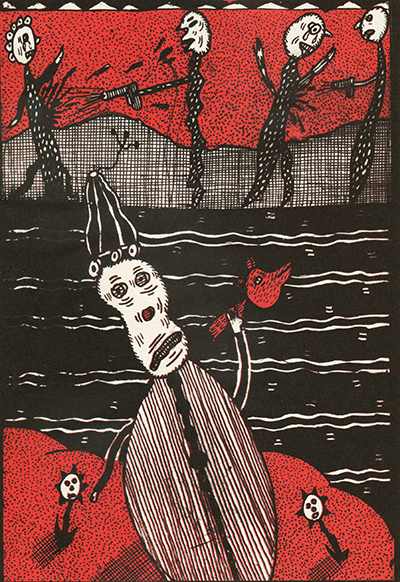

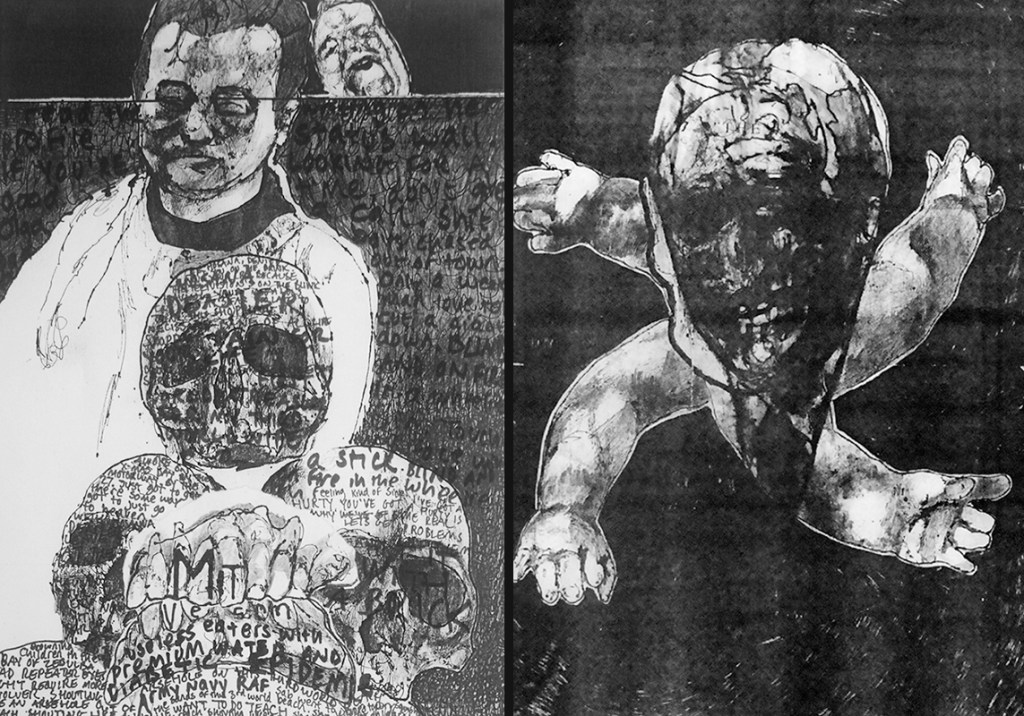

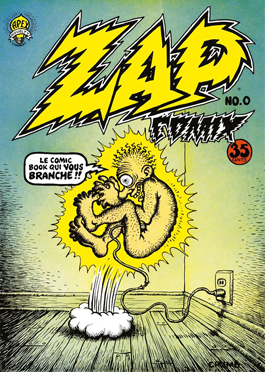

Longtime publisher Ron Turner of Last Gasp lets the red wine spill and herds some very wild cats

Longtime publisher Ron Turner of Last Gasp lets the red wine spill and herds some very wild cats

* ROLA

* ROLA