Highbrow Comics and Low Brow Art?

The Shifting Context of the Comics Art Object

Bart Beaty

In the thirty-two-page booklet that accompanies Gary Panter’s Limited Edition vinyl Jimbo doll, the artist includes a number of design notes and sketches that he sent to the sculptors at Yoe! Studios who crafted the maquette. According to these notes, Jimbo is six heads high; he should look more like Tubby from the Little Lulu comic book series than the warrior/adventurer Conan; and ideally he would come across as something between a toy by Bullmark, the Japanese company that produced soft vinyl Godzilla toys in the 1970s, and the more recent vinyl toys designed by Yoe! Studios based on old Kellogg’s cereal characters. In one of the longest exchanges recorded in the book, Panter takes an entire page to comment on the design of the doll’s penis, which on the original clay model ‘seemed a little high.’ With reference to classical figure drawing, Panter approaches the problem with a series of sketches, noting that if the penis sticks out too much ‘it will always be a joke,’ but that if it’s too little ‘guys will rib him at the gym.’ In the end, the artist has his way, and the Jimbo doll, limited to only 750 units, is produced with a prominent phallus, contained by a plaid loincloth held in position with a rubber band, and an unnatural pink paint colour that recalls, as the closing photo in the book points out, the colour scheme used on one of the many Hedora vinyl figures produced in Japan. In all then, the Jimbo doll knowingly melds hyper-masculinity, nostalgic collector culture, punk rock aesthetics, and Japanese toy monsters into one item. All of these elements meet at a critical juncture between the comics world and the art world. In other words, the Jimbo doll triangulates the precise status of comics art within the matrix of art and entertainment worlds. Indeed, the movement of Panter and his art through various circulatory regimes offers a significant opportunity to assess the contemporary status of comics as art.

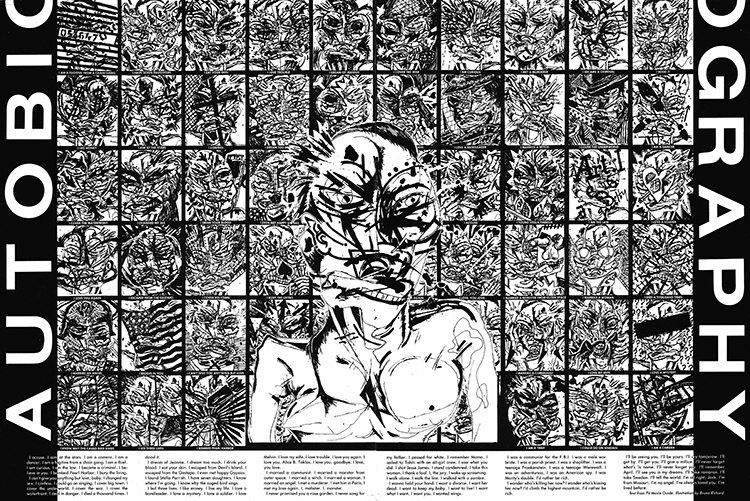

Panter, of course, is one of the most controversial of contemporary American cartoonists, and the reception of his work is often polarized. Writing in the PictureBox-produced catalogue of Panter’s paintings in 2008, the Los Angeles-based contemporary artist Mike Kelley argued that ‘Gary Panter is the most important graphic artist of the post-psychedelic (punk) period’ and further that ‘Gary Panter is godhead.’ Contrast that with the comments of Andrew D. Arnold, longtime comics critic for Time magazine, who derided Panter’s comic book Jimbo in Purgatory as the worst comic book of 2004 because it was ‘no fun’ and subsequently elaborated on that comment in a letter published in The Comics Journal: ‘I think Jimbo in Purgatory fails because it denies its audience a key function of its form: readability . . . Jimbo in Purgatory cannot be read in any involving way. It can only be looked at … Were Jimbo in Purgatory presented on the walls of a gallery, rather than a book, it would be inarguably remarkable. But in its chosen form, with the pretense of a story and characters but no reasonable entrée into them, the book fails in spectacular fashion.’ Arnold’s disdain for works that blur the boundaries of the gallery art world and a literary-minded comics world may be more widely shared than Kelley’s exuberant celebration of the genre-busting cartoonist, but it is a poor conceptual match for an artist who claims that ‘I’m aware of Picasso from beginning to end, just as I am aware of monster magazines and Jack Kirby. The intersections between them, in line, form, and populism provided the foundation for my artistic beginnings,’ and ‘I make the rules of the game that becomes my art.’

‘All this stuff is mashed together in my brain in a vein marked: Ultrakannootie, hyper-wild, ultra-groovy, masterfully transcendental beauty stuff.’ Gary Panter

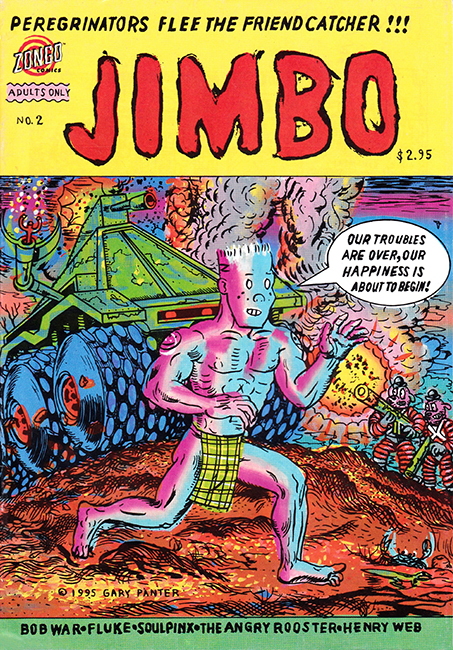

In the comics world, Panter is known as a significant progenitor of ‘difficult’ works and is the most public face of a ratty aesthetic that he pioneered and which has subsequently been adopted by artists affiliated with the small cutting-edge art cooperative Fort Thunder and with contemporary comics anthologies like Kramer’s Ergot and The Ganzfeld. One of the most important avant-gardists in American comics, Panter began contributing comics featuring Jimbo to the Los Angeles punk ’zine Slash in 1977, and soon thereafter self-published his first comic book, Hup. In 1981, Panter began publishing in Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s avant-garde comics anthology RAW with the third issue, for which he also provided the cover. Jimbo stories appeared in subsequent issues, and in 1982 Raw Books and Graphics published their first one-shot, a collection of Jimbo material on newsprint with a cardboard cover and duct-tape binding. Two years later, Panter published Invasion of the Elvis Zombies, the fourth RAW one-shot. At the time, Panter was working on a long-form graphic novel, Cola Madness, for a Japanese publisher, but that work was not published in English until 2000. The first of Panter’s Dante-inspired Jimbo works, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, was published in 1988 by Pantheon. At the time, the artist was best known for his work as the designer on the long-running children’s television series Pee-Wee’s Playhouse (1986–91). From 1995 to 1997 he published seven issues of Jimbo with Zongo Comics, a company owned by his friend and Simpsons creator Matt Groening. This series reprinted Panter’s earlier Dal Tokyo magazine strips and also launched his Divine Comedy material that was collected by Fantagraphics as Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006).

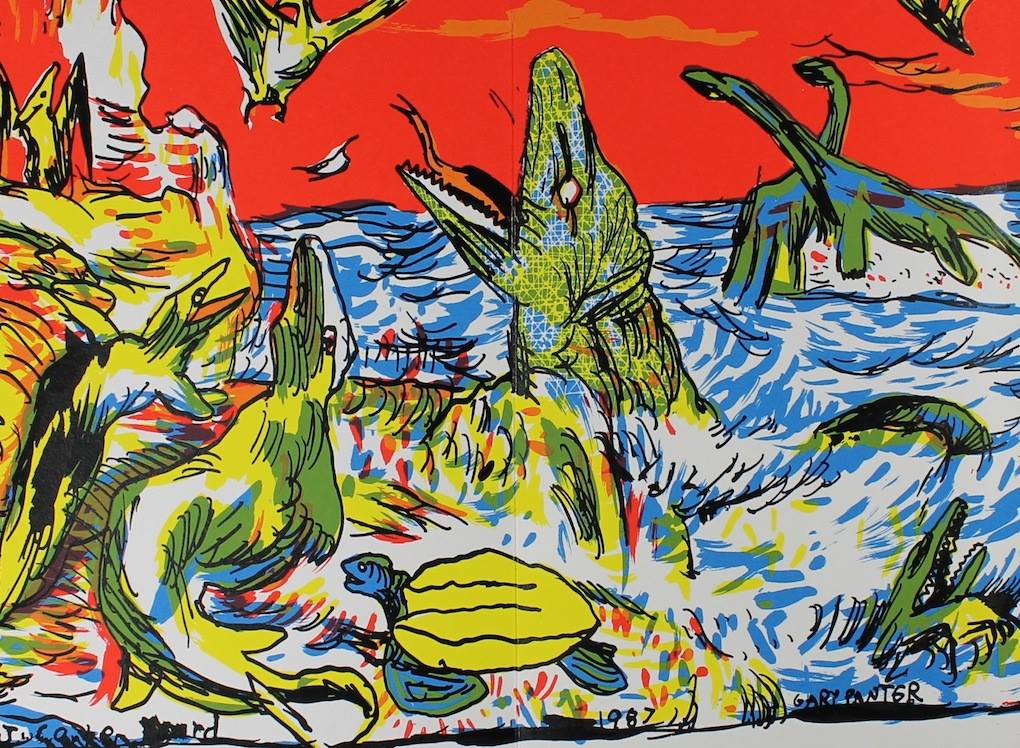

For all of his work in the comics world, Panter remains, as Arnold’s comments suggest, a somewhat marginal and liminal figure in the field. Panter himself has stated, ‘I still feel like a visitor to comics, but it’s a place I keep returning to in order to tell my stories.’ Significantly, in addition to his comics work, Panter has maintained a career as a painter, with dozens of solo and group exhibitions to his credit, and works as a commercial illustrator. His paintings display the influence of his generational compatriots (Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Kenny Scharf), as well as figurative artists of the 1960s (Eduardo Paolozzi, R.B. Kitaj, Öyvind Fahlström, Richard Linder, and Saul Steinberg), artists with a love of popular culture (H.C. Westermann and Jim Nutt), psychedelic-era collage artists (Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Alton Kelley, and Stanley Mouse), and the underground comics movement of the 1960s and its key figures such as Robert Crumb. By incorporating the examples of these extremely heterogeneous influences, ranging from lowbrow popular culture to esteemed modernist artists, Panter positioned himself, as he himself suggests, on the cusp of postmodernism, collapsing the distinctions between high and low culture. Despite these affinities with contemporary gallery painting, he told critic Robert Storr, ‘I think I’ve always been a wannabe in the art world’ because he was too shy to participate in much of the social scene that exists in that particular field. Thus, while he may be the outsider star in the less consecrated field of comics, Panter remains, by his own admission, merely marginalized in the field of gallery art. Examining the entirety of Panter’s creative output, as the PictureBox-published catalogue of his work does, foregrounds the fact that his work across a number of creative fields is the product of a singular vision, even as that work occupies very different positions in each field. The fact that his reputation

varies as his work circulates in different regimes is a stark reminder of how status in one field significantly impacts reputation in others.

RAW: Low Culture for Highbrows

The subtitle for the final issue of RAW, ‘High Culture for Lowbrows,’ sought to sum up the position occupied by artists like Gary Panter. Yet it can be convincingly argued that the historical relations between the comics world and the art world indicates that editors Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly inverted their key terms. For all intents and purposes, the primary audience for RAW was never lowbrow comics fandom; rather it was a world of cultivated art world highbrows. Michael Dooley argued in The Comics Journal that RAW ran the risk of ‘becoming the darling of the yuppie hipsters’ that sought in this comics anthology an outlet for cutting-edge, low-culture graphics. The istinction is not merely semantic, since it highlights the way in which the magazine is conceptualized and valued by its audience. Circulating in the art world more than the comics world, RAW’s audience was primarily an art world audience ‘slumming’ in the bleeding-edge margins of punk graphics. It was most assuredly not a magazine looking to bring a certain intellectual and cultural cachet to the lowbrow, juvenile audience long affiliated with the dominant American comic book traditions.

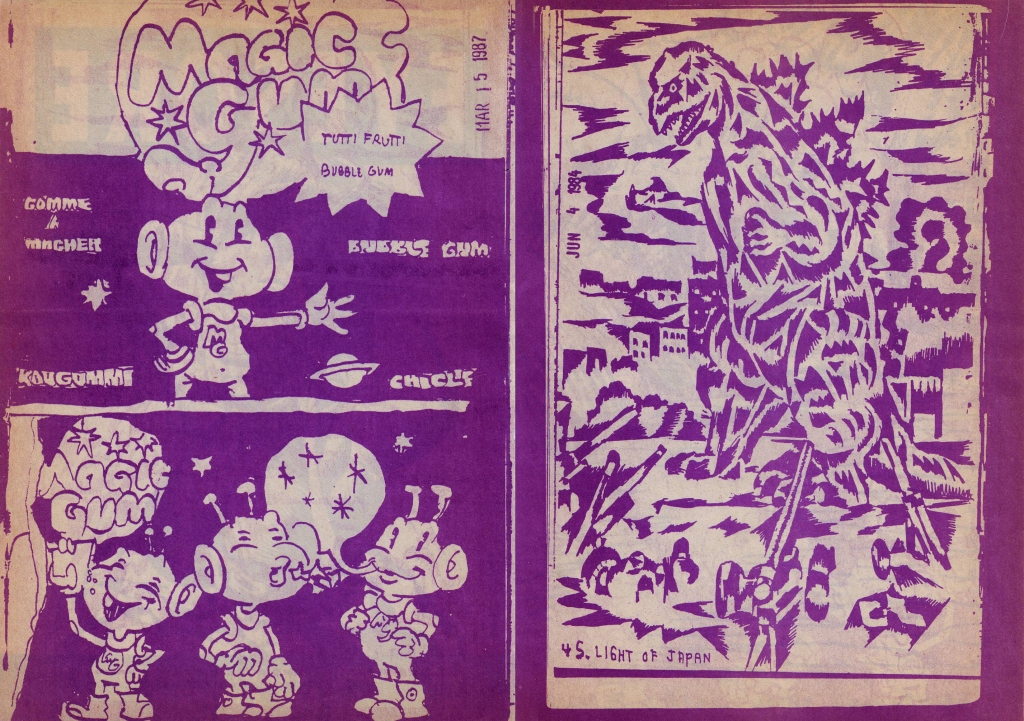

Best known as the venue in which Spiegelman serialized Maus, his award-winning autobiographical comic book, RAW was launched in 1980, four years after the death of Arcade, the late-era American underground anthology edited by Spiegelman with Bill Griffith. RAW’s first volume, comprising eight issues, was self-consciously at odds with both the mainstream American comic book tradition dominated at the time by superhero comics, and the underground’s sex and drugs countercultural sensibility. This difference was most strikingly marked by the magazine’s size, which owed a debt to Andy Warhol’s Interview and other publications targeting New York’s fashionable class. RAW was an oversized (10½” × 14″) magazine format ranging from thirty-six to eighty pages. Most issues carried a full-page ad for the School of Visual Arts, at which Spiegelman taught and some of the contributors studied, on their back cover, and later issues featured a series of small ads in the interior but were otherwise free from the taint of commerce. The first volume performed well outside of comics networks, including in record stores, and quickly sold out its print run of 5,000 copies. By the third issue, the print run had been expanded to 10,000. Several issues in the first volume contained notable features, including bound-in booklets for ‘Two- Fisted Painters’ and the individual Maus chapters by Spiegelman, as well as for ‘Red Flowers’ by Yoshiharu Tsuge. Other ‘collectables’ included Mark Beyer’s City of Terror bubblegum cards in #2, a flexi-disc of Ronald Reagan speeches in #4, and a corner torn from a different copy of the same magazine in issue #7. Although the indicia claimed it would be published ‘about twice a year,’ after the second issue RAW was, in actuality, published annually until 1986, when it went on hiatus. The anthology returned in 1989. The second volume of RAW was published by Penguin Books as a series of three smaller digest-sized (6″ × 8½”) anthologies of more than 200 pages. The later volume was entirely free of ads and circulated in both comic book stores and traditional book retailers. The second volume, by virtue of working with a publishing giant, had sales as high as 40,000 copies per issue and circulated as a Book-of-the-Month Club selection.

RAW focused on three types of comics: the historical avant-garde, contemporary international avant-gardes, and the American new wave comics sensibility, the last of which it largely came to define. Of these, historical works were clearly the least evident although in some ways the most important. The first issue of RAW contained a 1906 Dream of the Rarebit Fiend strip by Winsor McCay printed across two pages in which a suicidal man dreams of jumping from a bridge, only to bounce off the water and into the arms of a waiting police officer. Subsequent issues contained comics by the nineteenth century French caricaturist and satirist Caran D’Ache (Emmanuel Poiré), Milt Gross, Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton, Gordon ‘Boody’ Rogers, Gustave Doré, and, on two occasions, George Herriman. These selections allowed the editors to position RAW within a particular comics lineage that was at once international, highly formalist, and, given the interests and reputation of mid-century cartoonists such as Wolverton, Rogers, and Hanks, irreverently outside the mainstream of American comics publishing.

The international aspect of RAW was considerably more pronounced than its historical component, with a large number of non-American artists featured in every issue. Artists such as Joost Swarte, who provided two of eleven RAW covers, Jacques Tardi, Javier Mariscal, Kamagurka and Herr Seele, and Ever Meulen appeared regularly in the pages of the magazine. These artists, whose work clearly derived from the clear line style associated with Hergé, even as they radically reworked that style in their own unique ways, foregrounded a cosmopolitan comics heritage. At the same time, the aggressively pictorial work of the Bazooka Group (Olivia Clavel, Lulu Larsen, Bernard Vidal, Jean Rouzaud, Kiki and Loulou Picasso), Caro, and Pascal Doury pushed the magazine towards a highly self-conscious outsider aesthetic rooted equally in the poster art of the French punk music scene and situationist graphics. These works, which included some of the most non-traditional pieces ever published in RAW, situated the new wave graphics that the magazine championed as nothing less than a transnational movement. A similar effect was achieved when, in the seventh issue, RAW included Gary Panter in its special Japanese comics section (featuring work by Teruhiko Yumura, Yosuke Kawamura, Shigeru Sugiura, and Yoshiharu Tsuge) because his tote bags, drinking mugs, notebooks, and T-shirts are made and sold in Tokyo, and ‘he is the only RAW artist to have a snack bar in a Japanese department store named after him.’

Panter was not only an important linkage to the Japanese artists associated with the influential arts manga Garo, but was arguably the artist, aside from Spiegelman, most closely associated with RAW. Of course, Spiegelman himself, and many of the RAW cartoonists (Robert Crumb, Justin Green, Kim Deitch, S. Clay Wilson, Bill Griffith, and Carol Lay) were products of the underground comics movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, and many had published in the seven issues of Arcade. Nonetheless, RAW was perhaps best known for helping to launch the careers of a significant number of post-underground cartoonists, several of whom had been Spiegelman’s students and colleagues at SVA, including Drew Friedman, Mark Beyer, Kaz, Jerry Moriarty, Richard McGuire, Mark Newgarden, Ben Katchor, Charles Burns, Chris Ware, Sue Coe, Richard Sala, Robert Sikoryak, and David Sandlin. Of this generation, none was more integrated with RAW than Gary Panter, whose first work appeared in the pages of, and on the cover of, the third issue. One of only three artists to produce two covers for RAW, Panter published work in eight of the eleven issues, much of it featuring Jimbo, and authored two of the RAW published books.

‘I was SEDUCED! RAPED! I say more like KIDNAPPED, MOLESTED, and FOREVER PERVERTED! They poisoned a generation. I’M A LIVING TESTIMONY!’

Blab! Comics as Illustration

In several ways, not the least of which is the roster of artists that it supports, Blab! is an heir to the RAW project. Created by Monte Beauchamp in 1986, the same year as the final issue of RAW ’s first volume, Blab! is almost the inverse of RAW. The first seven issues (1986–92) were published in a small book format not unlike the size and shape of the second volume of RAW, but, starting with the eighth issue (1995), it expanded to a larger (10″ × 10″) format that would better accommodate Beauchamp’s growing interest in the relationship of comics, illustration, and contemporary design. Unlike RAW, which demonstrated a remarkable aesthetic purity over its run and an extremely consistent and singular editorial vision, Blab! has changed considerably over its more than two decades of publication. The first, self-published, issue was a nostalgic Mad fanzine. Opining from its opening pages that comics aren’t as good as they were in the 1950s when Bill Gaines was the publisher of EC Comics, Beauchamp recalled the earliest of organized comics fanzines when he reiterated the traditional fannish history concerning the damage done to the American comic book industry by Fredric Wertham and the ‘accursed comics code.’ 18 The rest of the issue was taken up by a series of written reminiscences about Mad from key figures in the underground comics movement, each testifying to the seminal influence that the satirical magazine had on the development of their thinking (Robert Williams: ‘I was SEDUCED! RAPED! I say more like KIDNAPPED, MOLESTED, and FOREVER PERVERTED! They poisoned a generation. I’M A LIVING TESTIMONY!’). The second issue was similar to the first, featuring an article on the Mars Attacks trading card set, a comic by Dan Clowes lampooning Fredric Wertham’s book The Show of Violence, and more written appreciations of Mad, this time from key figures in the emerging American new wave and alternative comics tradition, including RAW contributors such as Jerry Moriarty, Charles Burns, Mark Marek, Lynda Barry, and, of course, Gary Panter. Panter’s statement of influences in this issue (which include, among many others, Mad, Famous Monsters of Filmland, Piggly-Wiggly bags, Robert Crumb, Rick Griffin, Robert Williams, the Hairy Who, Henry Darger, toy robots, Jack Kirby, Claes Oldenburg, Walt Disney, George Herriman, and Pablo Picasso) was one of his earliest published statements about the diversity of influences, both high and low, that have structured his particular aesthetic point of view. Nonetheless, Panter, who published on only two other occasions in Blab! is not the major cross-over figure from RAW to Blab! With its third issue, now published by Kitchen Sink Press, the magazine became more evenly split between publishing comics by a mixture of new wave creators (Burns, Clowes, Richard Sala), underground artists (Spain), and outsider painters (Joe Coleman), alongside fanzine articles (Bhob Stewart on Bazooka Joe, and underground creators on the influence of Crumb). By the fifth issue (1990) the comics completely dominated the pages of the magazine, while the occasional essay or short fiction piece filled out the pages. Thus, over the first five years of its publication, Blab! elaborated a particularly forceful historical teleology that posited Mad as the root of American comics transgression and creative flowering, suggesting that it directly flowed into the undergrounds of the 1960s and that the new wave cartoonists of the 1980s were the obvious heirs to each of these legacies.

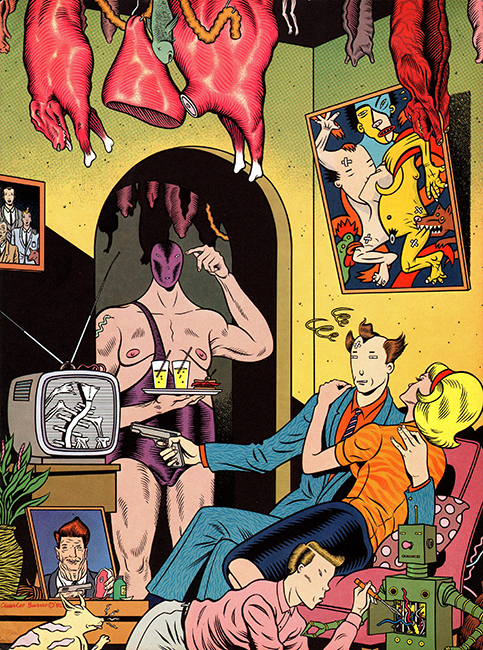

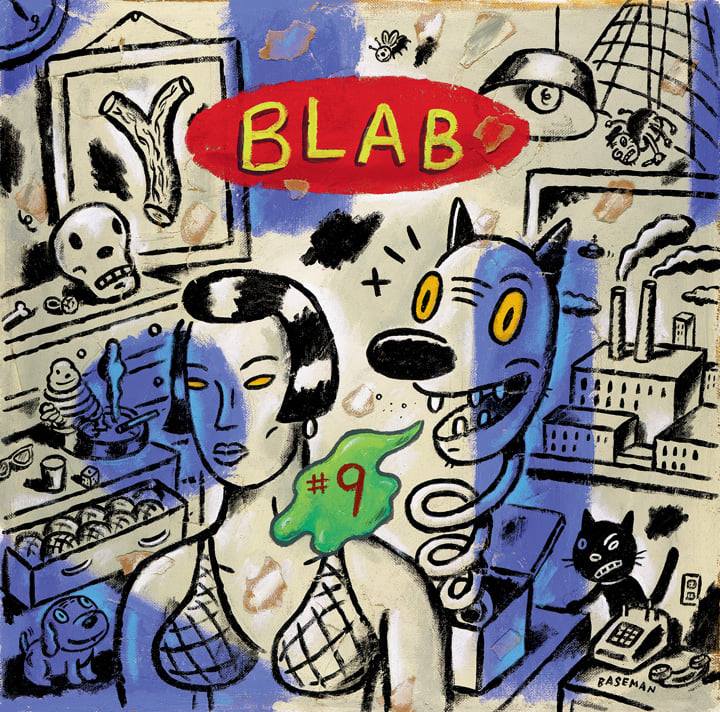

Having laid this foundation through its written articles, Blab! began the process of positioning itself as the specific heir to the traditions that it championed with its eighth issue (1995). Given a larger publishing format and better-quality paper, Beauchamp transformed Blab! into a showcase for new wave comics working at the intersection of commercial illustration and cutting-edge narrative forms. The eighth issue, in addition to work by regularly appearing cartoonists such as Sala, Spain, Chris Ware, and Doug Allen, reproduced celebrity magazine illustrations by RAW alumnus Drew Friedman and featured contributions from Gary Baseman, an illustrator significantly influenced by Panter. Baseman returned as the cover artist for the ninth issue (now published by Fantagraphics Books, after the bankruptcy of Kitchen Sink Press) and provided the end papers for the tenth, as he became a regular fixture in the magazine. Over the course of the next several years Blab! increasingly cultivated appearances by artists who, like Baseman, were loosely affiliated with the lowbrow painting movement influenced by Panter. Mark Ryden painted the cover for the eleventh issue, whose contents included work by the Clayton Brothers, Laura Levine, and Jonathon Rosen. Tim Biskup debuted in the twelfth issue, and Camille Rose Garcia and RAW alumnus Sue Coe both became regular contributors starting with the thirteenth.

Around this time Blab! became increasingly less interested in traditional narrative comics and much more aligned with cartoony tendencies in illustration and non-traditional approaches to comics storytelling (exemplified by the work of Finnish cartoonist Matti Hagelberg and Swiss cartoonists Helge Reumann and Xavier Robel). While classically formatted comics continue to persist in Blab! in the work of Greg Clarke, Steven Guarnacia, Peter Kuper, and others, the magazine is increasingly dominated by works that would, by the normative definitions of comics discussed in chapter 1, be deemed ‘not comics’ for their unusual wordimage balance, lack of panels, absence of storytelling techniques, and

other general weirdness. To this end, contemporary-era Blab!, even more than RAW, has pushed the boundaries of the comics form and helped to expand the conception of what constitutes legitimate avenues of expression in the comics world.

This tendency is even more pronounced in the books published by Blab! Beginning in 2005, Blab! like RAW before it, began publishing stand-alone books in a branded series. Significantly, the first of these, Sheep of Fools, featured the art of Sue Coe alongside the text of Judith Brody. Coe was firmly associated with RAW and had published two of the RAW one-shots, How to Commit Suicide in South Africa (with Holly Metz) and X (with Judith Moore). Similarly, the fifth Blab! book, Old Jewish Comedians, featured the work of RAW contributor Drew Friedman. Significantly, neither of these books would be classified as comics by traditional definitions of the form offered by critics and estheticians like Scott McCloud, despite the fact that each features the work of artists long affiliated with the comics industry, and both are published by a leading comic book publisher (Fantagraphics). Indeed, other books in the series do little to address the traditions of the field. Shag: A to Z by Shag ( Josh Agle) and David Sandlin’s Alphabetical Ballad of Carnality are each postmodern alphabetical primers, while Walter Minus’s Darling Chéri is a collection of softcore erotic drawings with a loosely attached text. The remaining books in the series, Struwwelpeter by Bob Staake and The Magic Bottle by Camille Rose Garcia, each draw on the illustrated text tradition more closely affiliated with children’s books, although their sexualized and violent adult content means that neither of these falls comfortably into that category. Thus, by rejecting the dominant formal traditions of comics, the books cement the transformation undertaken by the Blab! project, marking a particular historical lineage that culminates in the intersection of comics, art, and commercial illustration popularly known as lowbrow art. Ultimately, through the rejection of normative conception of comics, while remaining rooted in an ironic countercultural sensibility, Blab! positions a comics avant-garde through the embrace of what, in the world of painting, is known as lowbrow.

Resource: Bart Beaty, Comics Versus Art.Pdf

Great collection of Gary’s art work.

LikeLike